Sunday, March 4, 2012

Sunday Spinelessness - How could I forget Phronima?

Thankfully, other people done a much better job of celebrating these animals than I might have. Matthew Cobb wrote an article on them for Why Evolution is True, focusing especially on the salp whose body is stolen to form Phronima's house (you may be surprised to learn how closely related salps are to us). Mike Bok wrote a post about Phronima and the (perfectly plausible) idea that this creature was an inspiration for the design of the queen from Aliens. Finally, a clip from the extraordinarily awesome Plankton Chronicles series lets you see what I've been going on about with your own eyes:

Be sure to check out the rest of the videos in the series, which includes the flying snails I've blogged about before, a focus on salps in their own right, lots of jellies and all sorts of other wonderful creatures.

Labels: amphipoda, chordata, crustacean, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness

Sunday, February 19, 2012

Sunday Spinlessness - Amphipods are not prawns (and it matters)

Sadly, the New Zealand Herald managed to take just a tiny bit of gloss of the story. They choose to call the creatures "prawns" and illustrated their story with this picture...

Am I being ridiculously pedantic to care about this error? Is my life really so easy that I have time to worry about taxonomic and nomenclatural details associated with reports in the Herald? In fact, there's more to this error than the name. The Herald's conflation of these two distantly related groups highlights the way we fail to comprehend the true diversity of life on earth. So here's my attemp to show what you miss when you call an amphipod a prawn.

The scale of biodiversity

Every cell in my body is the result of an unbroken-chain of cell division that stretches back 3.8 billion years. I find that an absolutely staggering fact, but I shouldn't feel too special. Really, I 'm just like every creature on earth - riding on the edge of one of the lineages that extends out from biology's big bang at the origin of life. Plenty of people have tried to illustrate the history of life, here's one more look, based on DNA sequences from living organisms:

Forget animals and plants as the "two kingdoms" of life. For most of the history of life every creature on earth was a single cell. Even today, most of the lineages that extend out from the biology's big bang are made entirely of singled-celled organisms. Because this tree is based on those species that scientists have sequenced the genomes of, it drastically over-represents animals, but even here all animals are represented by the little twig that descending from the black-labeled node.

Biodiversity is more or less fractal, if we zoom in on that node and look at the phylogeny of animals we get another tree with branches:

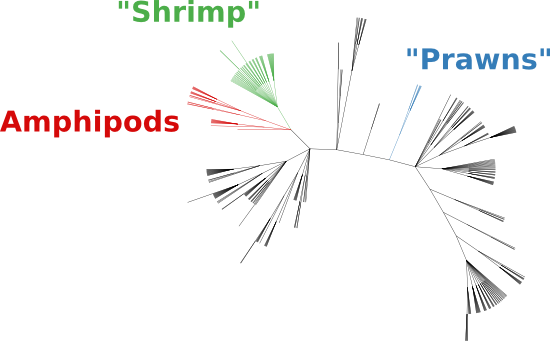

As I've said before, it's very difficult to resolve the relationships among the different lineages of animals. No matter how the branches relate to each other, it's clear there are a lot of different ways to be an animal, and that I'm never going to run out of subjects to write about for these Sunday posts. All the lions, tigers, bears, elephants, fish, fowl, lizards and frogs that make their way around the world with the aid of a backbone are part of the branch labeled Chordates above. The rest are invertebrates, and so fair game for me. But I'm meant to to be talking about amphipods, so let's skip a couple of steps and move into the arthropods (jointed-limbed creatures including insects) then down further into crustaceans and in particular the class Malacostraca - a group that includes crabs, lobsters, shrimps, wood lice and indeed amphipods and prawns:

So what is an amphipod?

Most marine amphipods look more or less like their land-lubber relatives. The super giants that showed up in the Kermadek Trench are presumably from the genus Alicella, which is related to, and more less a scaled-up version of, your typical scavenging amphipod. Other groups of amphipods have remained small, but radically reworked their ancestral body plan. The most striking example of such a reimagining are the elongated caprellids or "skeleton shrimp":

Caprella mutica. Photo is CC-BY-SA 3.0 from Hans Willewart

Cyamids are commonly called "whale lice", and indeed their flattened bodies are similar to those of their distant insect cousins:

All the trees here were made with iTOL, this first is their main tree drawn unrooted. The animal and Malacostraca trees are the NCBI taxonomy drawn to phylum and genus level respectively

Labels: amphipoda, crustacean, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness, taxonomy

Sunday, August 8, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - In the news

Spineless creatures have been all over the news this week. We've had strange beasts appearing on beaches, wondrous finds from the deeps and (apparently) a new front on the war on cancer.

Let's start here in New Zealand with a surprising find on a Wellington beach.

Photo from stuff article /Emma Best

That's a giant squid (Architeuthis sp.) and at 3m long it's a baby, full grown females can reach 13m. Giant squids are really deep sea predators, so beachings are relatively rare. This one appears to have been in a fight. We don't know too much about the food webs at the bottom of the ocean, sperm whales are the only creatures known to take on adult giant squids but sharks and other whales might very well attack sub adults like this one. As an aside, studying parasites might be the best way to work out who eats who in the deeps. When you dissect a shark or a whale its stomach contents give you a picture of what it's eaten recently, when you look at its parasites you can paint a picture of what it's eaten over its lifetime. However the squid got its injuries, they proved fatal. it washed up dead and was returned to the ocean with the next high tide.

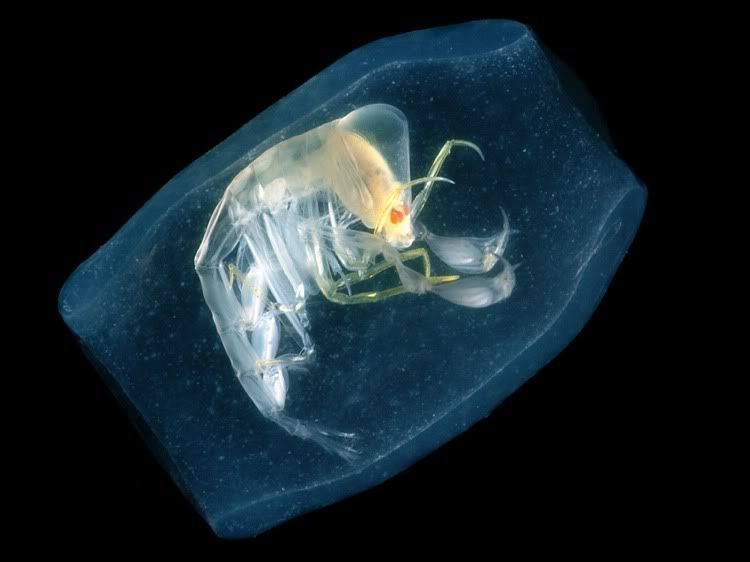

Then there was the announcement of the results of the Census of Marine Life, an inventory of the species living in the earth's oceans. The news of that story was almost universally illustrated with pretty pictures of weird animals photographed from deep sea submersibles. Here's a particularly striking example of the genre, an amphipod with a house which showed up in the Guardian and National Geographic:

Photo from Texas A&M press

Obviously, that mean-looking shrimp-like amphipod is a spineles creature, but it might suprise you that its transluscent home is also an animal. In fact, it's one of your closest relatives in the biological world. It's a salp, a relative of the sea squirts, and it's a member of the chordata - the same phylum as the all the vertebrates. Matt Cobb has all the details in his guest post at why Evolution is True.

Finally, scientists published the first complete genome sequence from a sponge. As has become customary for genome studies, the press releases and the resulting new stories all suggest that these DNA sequences will help us fight cancer. Well, perhaps. Cancer is ultimately about uncontrolled cell proliferation and sponges are the simplest animals to have to find a way of marshalling thousands of cells into a single body. But is that really the only reason we should be exciting about a tool that helps us to understand the origins of multicellularity, or being able to see where the precursors of the development programs that pattern the bodies of more complex animals came from? I'd like to think the average reader is just an excited by a little scientific awe as they are by some ill defined and far off medical benefit. (Before I sound too grumpy I should say that the press release from UC Santa Barbara was really very good, it's just a shame some of those points didn't get picked up in the reporting.)

To those three stories you can add a call for insects to replace red meat, sub zero octopus venom and a BBC tour of invertebrate collections form the Gulf of Mexico. It really was quite the week for invertebrate news.

Labels: carnivorous sponge, crustacean, genomics, molluscs, porifera, salp, sci-blogs, squid, sunday spinelessness