Sunday, November 14, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - My own ID challenge

Some of the cooler kids in bug-blog world post identification challenges from time to time (1,2,3). I seldom get very far on those challenges, in fact, they usually serve only to make me wonder if there is any obscure insect group Ted McRae can't ID from a single photo.This month I've had my own little ID challenge sitting out in the garden, the Pittosporum is infested with these:

Sadly, I have to admit I didn't even recognise these guys as animals on the first take (the greatest taxonomy fail ever?). Just passing by the bush it's easy to mistake the dark patches for some sort of of blemish within the leaves themselves. But blemishs don't tend to move, and they're not usually so unerringly associated with winged bugs:

The 'blemishes' must actually be flattened sap-sucking nymphs on their way to becoming the adults on the left. "Flattened sap-sucking nymphs" sounds a lot like scale insects. Scales are a diverse group of true bugs known to gardners because one group, the mealy bugs, are a fairly common plant pest. In New Zealand, scale insects are of immense ecological importance. Ultracoelostoma scales live within the bark of Southern Beech (Nothofagus spp.) trees. These scales act like little siphons, they stick their mouths into the phloem (the sap) of the tree while the other end of their digestive tract extends out from the tree's trunk on a long waxy filament. The excreted sap, which is still very energy-rich, forms in a droplet at the end of the anal filament. If the sugary droplet stayed at the end of the filament for too long it might harden, and prevent the flow or more sap into the scale insect's body. There isn't much risk of that happening though, the 'honeydew' provided by scale insects is a valuable food source in beech forests (which are usually short on fruit and flowers). Nectar eating birds, including the tui, bellbird and kaka, visit trees every few minutes to drink the scale insect's honeydew.

Sadly, these days introduced yellow jacket wasps are probably even more frequent visitors to scale insects. A healthy beech forest can support 10 000 of these social wasps per hectare (about ten times the density they reach in the Northern Hemisphere), that's a big enough army of wasps to take the honeydew resource away native birds and to go on and kill thousands of native invertebrates. (Landcare Research have page explaining the beech scale insect and the impact of wasps)

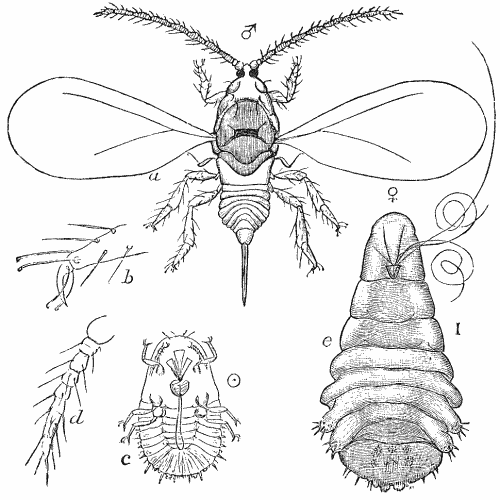

But that's all an aside, because the nymphs on my Pittosporum can't be scales. Scales are one of the few animals I can think of in which one sex doesn't develop as far as the other. The long maintaince of juvinile characters in adult organisms is called neoteny (the axolotl, a salamander that never metamorphoses but still reproduces, is probaly the most familar example of this phenomenom). In scale insects the adult female looks for all the world like those flat-bodied nymphs, while the adult is a two-winged bug (which looks... like nothing else really). There is a diagram of the adult scales in Project Gutenberg's version of The Life Story of Insects:

I have reason to belive that the adult females on our Pittosporum look aobut the same as the adult males:

Actually, the fact these guys are living on the Pittosporum should have been the give away to what they are. Plant sucking insects often become highly specialized, with species adapting to a particular host plant. These insects are the most common Pittosporum pest species Trioza vitreoradiata, the Pittosporum pysllid*. Apart from the fact the psyllids are related to aphids and scales and few other primative true bugs I can't tell you a lot more about them. Apparently they make good eating, I've seen worker ants and this fly abscond with nymphs:

I've also noticed one other, quite endearing habit. Almost any time one of the adults moves they do so by pointing their head down and their butt up and wiggling. Here, for the first time, is the psyllid boogie recorded for your viewing pleasure (this particular performance was delivered on my outstretched hand, which this psyllid thought would be a safe place to escape to when it got sick of having a camera in its face):

*This isn't a particularly accurate name. Pysllid is a name describing members of the family Psyllidae, but most recent taxonomies have placed Trioza in a separate family. Both are still in the superfamily Psylloidea, so I guess they should be called psylloids, which sounds even more sci-fi then there usual name.

Labels: bugs, environment and ecology, photos, psyllids, scale insects, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness

4 Comments:

The feasting fly may be a Dance Fly - Empididae.

Do you mean 'nymph' is old fashioned in general, or just for these bugs? I still see it a lot, but I don't read entomological journals so I could just be reflecting older names.

Thanks for the heads up on the fly, I can never get anywhere with IDing anything other than crane flies and hover flies in the backyard.

For general works, it may have been Penny Gullan and Pete Cranston's first edition of The Insects that started using larva for all. Naiad (which I was taught for mayflies, odonates, etc.) seems to be obsolete and nymph obsolescent, although some still use the term. As I understand it, the argument is that too much emphasis has been placed on what we see – the morphology of the developmental stage – rather than on the process that is going on. I asked Bruce Heming about this – he’s into physiology and development – and he suggested reading:

Minelli et al. 2006. From embryo to adult—beyond the conventional periodization of arthropod development. Dev Genes Evol 216: 373-383.

and also: pp. 1-4 in Vol. 1 of Fred Stehr's Immature Insects.