Tuesday, May 29, 2007

Meanwhile, on another planet

The other day I posted a brief run down of a few of things that happened in the real world while I was away. I focused on sciency things and bits and pieces that I thought were interesting and noteworthy. What I didn't talk about was the political blag-o-verse, which appears to be designed to make talk back radio look like a forum for well reasoned arguments. So here are some of the very strange things people have been up lately:

- A group of American "conservatives" became so disgusted with

realitywikipedia's 'liberal bias' (like using international English spellings and replacing BC with BCE in attempt to remove Jesus from discussion of Greek history) that they saw no option but to set up their own truth and call it conservapedia. This new wiki is, of course, free of bias of any type - We have anti-science nutcases in New Zealand too. Ian Wishart, differencephobe, editor of Investigate magazine, self promoter (of faint praise) and owner of many books - mostly hard-bound, thinks that evolutionary biology is on its last legs because one character that was thought to have evolved three times in insects with membranous wings has actually evolved four times. And because 300 engineers and computer scientists say so and presumably because he's been praying real hard for it. Can't wait to get a copy of that book (which is more popular even that 101 things to do with a slow cooker. Take that Richard Dawkins!)

- The Pope announced he was catholic (no word from bears as regards their defactionary habits) and a little bit confused. Catholics announced the Pope we was being very sensible.

- But anti-science isn't just for creationists anymore! Out right denial of global warming is getting harder to find, but we have on these rare birds in Whaleoil who thinks that an hour tapping away on the keyboard probably qualifies him to teach climatologists a thing or two (debunked here) because climatology has something to do with weather forecasts (debunked here) and is totally like phlogiston because it has no checks and balances (debunked here)

- Cynicism is the new skepticism in global the global warming debate, see David Farrar who thinks that since the biggest forest fires in a hundred years release about as much CO2 as one state in one country for one month which is then absorbed in new forests we should probably not bother to limit our own emissions. Or something. And besides, much like our stance on human rights and fair trade, we probably shouldn't bother doing anything until China does

- At least everyone can agree a single record of temperature is of no particular importance when we are talking about global trends in temperature. Unless of course it's a cold one.

- I have to admit that a little bit of me is happy that the most egregious attack on common sense, rationalism and scholarship is at the expense of history and not science. Lucyna (yes, an anagram of lunacy...) has found an appalling piece of crypto-history called the Pink Swastika that picks through obscure sources, quotes real historians selectively and jumps on the speculations of less reputable authors to make a case that The Third Reich was a vast homosexualist conspiracy. She has also been seen arguing the case that modern scholars think the gospels were written by the actual apostles of Jesus, that the contradictions in those gospels are proof that their story is real ( because who would make something that weird up) and any number of other things

Just like last time this isn't an exhaustive list of the strange an irrational things people have done recently, just a litte taste of whats out there if you're foolish enough to look.

Friday, May 25, 2007

Thoughts on an encyclopedia of life on Linneaus' 300.005th birthday

The little review of 'things that have happened recently' might also have included some of the buzz that has surrounded the launch of The Encyclopedia of Life (already denoted by the TLA EoL I see). If you're coming late to the party a very impressive group of organizations and individuals have got together to produce "an online reference source and database for every one of the 1.8 million species that are named and known on this planet". Add to this news the fact that Wednesday saw the celebration of Carolus Linnaeus' 300th birthday and you'll see I'm left with no choice but to talk a little about how 21st taxonomy is going to have to shape up if it is to fulfill Linnaeus' dream of describing every species on earth.

The Enclyopedia of Life wants to have a page for each of the 1.8 million species described since Linnaeus started the job. This is great, and an admirable goal, but 21st century taxonomy has a much greater task before it. There are probably another 10 million species on earth that haven't been described. Finding, naming and describing all these unknown species isn't just a biological stamp collecting exercise. The earth is in the grip of it's sixth great extinction and the organisations that governments have assigned to stemming this lost don't even know that 80% of the species they are meant to protect exist! The problem is even worse, taxonomy is not a sexy science and funding for expert taxonomists has dried up in recent years so now there are only a limited number of taxonomists in the world who can identify named species and start describing new ones and each of them are necessarily specialists in only one branch of the tree of life.

So, can a project like the EoL help bridge the so called taxonomic impediment? It has to be said we have very little of the details of the project but I'm optimistic. If the encyclopedia is going to be more than a mash up (their phrase) of existing projects it could develop into tool which taxonomists can share high resolution images and ecological, biogeogaphical and genetic data. Every major museum has a backlog of samples waiting to be sorted and assessed by taxonomists, a major database and network that allows the secrets those samples hold to be uncovered would be going along way to finishing what Linneaus started

Labels: taxonomy

Thursday, May 24, 2007

While I was out...

I've been not-blogging (my own, very lazy, response to cat-blogging, mo-blogging, vid-blogging and of course weird-sex-blogging) for some time now. It comes as some surprise to me to see that quite a few things happened on the internet in my absence.

- Bloggers blitzed biomes across the world and found any number of cool things. A similar, but unrelated, event found a whole new species of weta in Otari bush, right in the middle of suburban Wellington

- Even cooler than a new weta, a fossil bed in central otago that had already allowled us to glimpse a New Zealand covered by Protea and Eucalyptus and populated by snakes and crocodiles gave us the first evidence of a terrestrial mammal in Aoteoroa 'Kingdom of Birds'.

- I became a for real, published scientist. More to come on that one.

- Paul Litterick and the Rationalists parted ways citing creative differences. Thankfully Paul has continued the Fundypost as a solo project. The new 'post draws on artistic, new wave and post punk influences to arrive at its own voice and is sure to become a cult classic.

- Harvest Bird comments at the Fundypost. She also teaches, links to cool things, writes rather well, and has puppies, so that's nice.

- Coturnix (question for biologists - do you italicise a Genus' name when the word not is being used to talk about the genus in question?) has continued to blog a mile a minute, even keeping track of impossibly protracted argument about framing science and getting a book published. And just today he got a job for all his hard work!. Congratulations Bora, it's hard to imagine someone better equipped to do it.

- Afarensis has started a neat series on posts on the experiments of Charles Darwin, can't wait till he gets up to the worm book

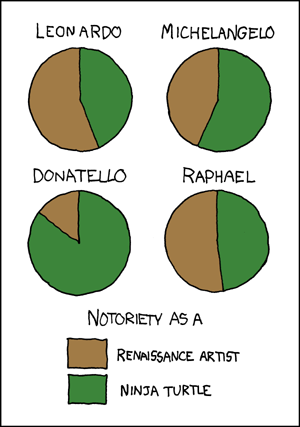

- I discovered xkcd (and read the whole archive in the same day)

I imagine quite a few other things happened and that if I wrote this post on any other day it would be quite different. Anyway, since all the cool kids are including videos at the end of their posts a these days and it is NZ music month, here are Cut of Your Hands (formerly known as shaky hands) with Expectations (and balloons):

Autumn in Dunedin

Dunedin’s all too short a lease on summer is running out. The bare chested, beer guzzling boys that made Castle Street their cricket pitch have found hoodies, high school leavers jerseys and rugby balls. Students they have been around Dunedin long enough to know are reconciling themselves with the city’s slide into a winter of cold dark mornings followed quickly by cold dark evenings. Even the trees around campus are hunkering down. . The chemical cascades that ran wild in leaves through the summer to capture the sun’s energy are grinding to a halt. Keeping these reactions going through the winter would cost more energy than they could generate so the leaves, like middle management closing down an unprofitable branch, let the leaves fade and fall.

The autumn displays that deciduous trees put on are rightly held up as an example of the great beauty in the natural world. Until recently the scientific understanding of these displays has been entirely more prosaic. The green, light catching pigment chlorophyll is hard to make and as such a valuable resource for a tree. Before the tree cuts its leaves free it strips their assets - taking all the chlorophyll out to reinvest it in the next season’s crop. With the very green chlorophyll removed red and brown pigments (always present but previously swamped by the chlorophyll) shine through and you get autumn colours. However, over the last few years another theory has challenged this idea and enlivened scientific interest in the phenomena occurring around Dunedin at the moment.

The new theory is among the very last from W. D. Hamilton, one of the 20th century’s greatest biologists. When Hamilton died in 2000 he was eulogised as “the most distinguished Darwinian since Darwin” and generally lauded for the way his insightful, almost whimsical (he once proposed clouds were generated by bacteria as a way of spreading themselves) ideas revolutionized biology. Hamilton was a key figure in a generation of English biologists that sought to describe almost everything in nature, including humans and our behaviour, as the result of evolution by natural selection and in so doing formed the ‘adaptationist school’ of evolutionary theory. Hamilton’s greatest contribution to this effort was to show that seemingly altruistic behaviour by an organism towards its relatives (including parental care) can be explained in terms of natural selection acting at the level of genes. This theory formed an important part of Richard Dawkins’ bestselling popularisation The Selfish Gene

Later in life Hamilton focused on another evolutionary mystery. Sexual reproduction seemed counterproductive in the genetic understanding of evolution he had helped to usher in. If each individual is acting to maximise the amount of genetic material it passes to the next generation then putting only half of your genes into each child and having half of those offspring themselves unable to bear more young (that is to say being male) seems a silly idea. As Hamilton’s colleague John Maynard Smith pointed out sexually reproducing organisms must reap some evolutionary advantage over asexually reproducing ones or evolution would favour a return to asexuality (as has happened in many lineages). Hamilton believed that sexual reproducing organisms may be reaping that reward in the constant and expensive wars they wage with parasites. By mixing their genes with each other organisms may be able to make novel weapons in that fight that asexual clones couldn’t arrive at. The first support for this idea from nature came from lakes right here in New Zealand’s South Island. The tiny snails you find clinging to rocks in our lakes are a perfect model in which test Hamilton’s ideas because they are heavily parasitized in some areas and not in others and because some lineages reproduce sexually and others have given up on that idea and reproduce by cloning. In 1987 Curt Lively showed that sexually reproducing snails occurred where parasitisation was at its densest while asexual ones survived in higher numbers where parasitism was low. This is exactly what Hamilton’s theory predicts – sexually reproducing lineages are gaining an edge in parasite heavy lakes while asexual lineages prosper when they don’t have to fight many parasites

Much of Hamilton’s later worked centred on important the role of parasites in evolution, he went so far as to suggest they may explain the peacock’s ostentatious tail. He theorised that only males that were free of parasites and by extension healthy could invest in such elaborate displays. Shrewd peahens would therefore select partners with the most over-the-top tails to ensure their offspring got the best parasite fighting genes. In other words, to Hamilton a peacock’s tail was a gawdy advertisement for its owner’s genes.

He even thought parasites might explain autumn colouration. In a paper published posthumously in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Hamilton argued that deciduous tree’s autumn displays might represent an advertisement similar to a peacock’s. In his theory autumn colours are actually a tree’s way of telling parasitic insects that the tree is so healthy it can stop photosynthesising early and invest in bright red and yellow colouration as a warning. A tree that is strong enough to give up it’s energy making process early must surely be strong enough to invest in the many measures trees take against their parasites so a prudent insect will stay well clear of such a tree when it some time to lay its eggs.

One of the hallmarks of a good scientific theory is testable predictions. Hamilton’s signalling hypothesis makes several predictions, many of which are gaining experimental support. First, if the yellow and red leaves are indeed a signal to be taken seriously by potential parasites then we would expect only healthy trees could invest in colouring their leaves at the time the parasites arrive. One good marker for the health of a tree is how symmetrical that tree’s leaves are – healthy trees produce nice symmetrical leaves while trees under stress make more irregular ones. In 2003 Norwegian researchers took yellow and green leaves from birch trees in early autumn. According to Hamilton’s theory only the healthy trees will be investing in yellow leaves so, on average, the yellow leaves will be more symmetrical. When the researchers measured the leaves this is exactly what they found.

If autumn colours are a signal for insects and they would need to be made when infection by parasitic insects was likely. Swiss researchers confirmed in 2004 that deciduous trees in that country change colour when aphids start to lay eggs (which will hatch in spring when the trees produce sugar rich sap) Thirdly, if the signal is actually heeded by insects we would presume those aphids in fact steered clear of the trees making the strongest displays and picked the ones that were still green. The same Swiss team and a number of other investigators have reported that aphids show a strong preference to laying their eggs on green leaved trees. Finally, and most obviously, Hamilton’s theory also suggests that the healthy trees that invest in signals suffer less at the hands of parasites in the following spring. This prediction was born out in 2003 Norwegian study.

All this speaks strongly for the veracity of Hamilton’s signalling hypothesis. Still, a great number of scientists remain sceptical and number of related and unrelated theories has been proposed in response to Hamilton’s. Which ever theory turns out to be true Hamilton’s signalling hypothesis is one of the last gives from one of the greatest minds in biology. He took one of the most mundane stories in biology – fiscal dowdiness on the part of trees – and enlivened it. In Hamilton’s view the hills around Dunedin are on fire with warning shots from and evolutionary cold war, a fine example of how a little insight to the workings of biology can add yet more beauty to the natural world.

Sadly, it seems Hamilton's theory may be, in the word of TH Huxely, "that great tragedy of Science - the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact". Check out what Carl Zimmer (whose blog put me on to this story in the first place) has to say on it.

Dunedin’s all too short a lease on summer is running out. The bare chested, beer guzzling boys that made Castle Street their cricket pitch have found hoodies, high school leavers jerseys and rugby balls. Students they have been around Dunedin long enough to know are reconciling themselves with the city’s slide into a winter of cold dark mornings followed quickly by cold dark evenings. Even the trees around campus are hunkering down. . The chemical cascades that ran wild in leaves through the summer to capture the sun’s energy are grinding to a halt. Keeping these reactions going through the winter would cost more energy than they could generate so the leaves, like middle management closing down an unprofitable branch, let the leaves fade and fall.

The autumn displays that deciduous trees put on are rightly held up as an example of the great beauty in the natural world. Until recently the scientific understanding of these displays has been entirely more prosaic. The green, light catching pigment chlorophyll is hard to make and as such a valuable resource for a tree. Before the tree cuts its leaves free it strips their assets - taking all the chlorophyll out to reinvest it in the next season’s crop. With the very green chlorophyll removed red and brown pigments (always present but previously swamped by the chlorophyll) shine through and you get autumn colours. However, over the last few years another theory has challenged this idea and enlivened scientific interest in the phenomena occurring around Dunedin at the moment.

The new theory is among the very last from W. D. Hamilton, one of the 20th century’s greatest biologists. When Hamilton died in 2000 he was eulogised as “the most distinguished Darwinian since Darwin” and generally lauded for the way his insightful, almost whimsical (he once proposed clouds were generated by bacteria as a way of spreading themselves) ideas revolutionized biology. Hamilton was a key figure in a generation of English biologists that sought to describe almost everything in nature, including humans and our behaviour, as the result of evolution by natural selection and in so doing formed the ‘adaptationist school’ of evolutionary theory. Hamilton’s greatest contribution to this effort was to show that seemingly altruistic behaviour by an organism towards its relatives (including parental care) can be explained in terms of natural selection acting at the level of genes. This theory formed an important part of Richard Dawkins’ bestselling popularisation The Selfish Gene

Later in life Hamilton focused on another evolutionary mystery. Sexual reproduction seemed counterproductive in the genetic understanding of evolution he had helped to usher in. If each individual is acting to maximise the amount of genetic material it passes to the next generation then putting only half of your genes into each child and having half of those offspring themselves unable to bear more young (that is to say being male) seems a silly idea. As Hamilton’s colleague John Maynard Smith pointed out sexually reproducing organisms must reap some evolutionary advantage over asexually reproducing ones or evolution would favour a return to asexuality (as has happened in many lineages). Hamilton believed that sexual reproducing organisms may be reaping that reward in the constant and expensive wars they wage with parasites. By mixing their genes with each other organisms may be able to make novel weapons in that fight that asexual clones couldn’t arrive at. The first support for this idea from nature came from lakes right here in New Zealand’s South Island. The tiny snails you find clinging to rocks in our lakes are a perfect model in which test Hamilton’s ideas because they are heavily parasitized in some areas and not in others and because some lineages reproduce sexually and others have given up on that idea and reproduce by cloning. In 1987 Curt Lively showed that sexually reproducing snails occurred where parasitisation was at its densest while asexual ones survived in higher numbers where parasitism was low. This is exactly what Hamilton’s theory predicts – sexually reproducing lineages are gaining an edge in parasite heavy lakes while asexual lineages prosper when they don’t have to fight many parasites

Much of Hamilton’s later worked centred on important the role of parasites in evolution, he went so far as to suggest they may explain the peacock’s ostentatious tail. He theorised that only males that were free of parasites and by extension healthy could invest in such elaborate displays. Shrewd peahens would therefore select partners with the most over-the-top tails to ensure their offspring got the best parasite fighting genes. In other words, to Hamilton a peacock’s tail was a gawdy advertisement for its owner’s genes.

He even thought parasites might explain autumn colouration. In a paper published posthumously in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Hamilton argued that deciduous tree’s autumn displays might represent an advertisement similar to a peacock’s. In his theory autumn colours are actually a tree’s way of telling parasitic insects that the tree is so healthy it can stop photosynthesising early and invest in bright red and yellow colouration as a warning. A tree that is strong enough to give up it’s energy making process early must surely be strong enough to invest in the many measures trees take against their parasites so a prudent insect will stay well clear of such a tree when it some time to lay its eggs.

One of the hallmarks of a good scientific theory is testable predictions. Hamilton’s signalling hypothesis makes several predictions, many of which are gaining experimental support. First, if the yellow and red leaves are indeed a signal to be taken seriously by potential parasites then we would expect only healthy trees could invest in colouring their leaves at the time the parasites arrive. One good marker for the health of a tree is how symmetrical that tree’s leaves are – healthy trees produce nice symmetrical leaves while trees under stress make more irregular ones. In 2003 Norwegian researchers took yellow and green leaves from birch trees in early autumn. According to Hamilton’s theory only the healthy trees will be investing in yellow leaves so, on average, the yellow leaves will be more symmetrical. When the researchers measured the leaves this is exactly what they found.

If autumn colours are a signal for insects and they would need to be made when infection by parasitic insects was likely. Swiss researchers confirmed in 2004 that deciduous trees in that country change colour when aphids start to lay eggs (which will hatch in spring when the trees produce sugar rich sap) Thirdly, if the signal is actually heeded by insects we would presume those aphids in fact steered clear of the trees making the strongest displays and picked the ones that were still green. The same Swiss team and a number of other investigators have reported that aphids show a strong preference to laying their eggs on green leaved trees. Finally, and most obviously, Hamilton’s theory also suggests that the healthy trees that invest in signals suffer less at the hands of parasites in the following spring. This prediction was born out in 2003 Norwegian study.

All this speaks strongly for the veracity of Hamilton’s signalling hypothesis. Still, a great number of scientists remain sceptical and number of related and unrelated theories has been proposed in response to Hamilton’s. Which ever theory turns out to be true Hamilton’s signalling hypothesis is one of the last gives from one of the greatest minds in biology. He took one of the most mundane stories in biology – fiscal dowdiness on the part of trees – and enlivened it. In Hamilton’s view the hills around Dunedin are on fire with warning shots from and evolutionary cold war, a fine example of how a little insight to the workings of biology can add yet more beauty to the natural world.

Sadly, it seems Hamilton's theory may be, in the word of TH Huxely, "that great tragedy of Science - the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact". Check out what Carl Zimmer (whose blog put me on to this story in the first place) has to say on it.