Sunday, August 5, 2012

Sunday Spinelessness - How snails conquered the land (again and again)

Christie Willcox wrote a

nice article this week on how one small group of organisms called "vertebrates" first evolved to live on land. Since you are a vertebrate who lives on land, you should probably go and read Christie's piece. I wouldn't want you, however, to go around thinking those first fish to leave the ocean behind were pioneers making a uniquely difficult transition. By my figuring, onycophorans (velvet worms like

peripatus), tardigrades, annelids, nematodes, nemerteans (

ribbon worms) and quite a few arthropod lineages have also taken up a terrestrial lifestyle. Many of those lineages were already breathing air before

Tiktaalik, Ichthyostega and your other long-lost relatives

came along to join them on land. But if you want to talk about transitions from marine to terrestrial lifestyles then you really want to talk about snails. You can find snails living in almost every habitat between the deep ocean and the desert, and snails have adapted to life on land many different times. In fact, a litre of leaf litter taken from a New Zealand forest can contain snails representing three separate transitions from water to land.

Almost all the land snails I've talked about here at

The Atavism are descendants from just one invasion of the land. We call these species the

stylommatophorans and you can tell them from other landlubber-snails because they have eyes on stalks (as modeled here by

Thalassohelix igniflua):

These snails are part of a larger group of air-breathing slugs and snails (including species living in fresh water, estuaries and even the ocean) called pulmonates or "lung snails". As both the common and the scientific names suggest, pulmonates breathe with lungs. Specifically, the mantle cavity, which contains gills in sea snails, is perfused with fine veins that allow oxygen to permeate the snails's blood. In relatively thin-shelled species you can often see this "vasculated" tissue in living animals:

Blacklight photo of

Cepaea nemoralis showing 'vascularised' lung. Photo is

CC BY-SA via Wikipedian

Every1Blowz

The pulmonates can also regulate the amount of air entering their lungs with the help of an organ called the pneumatostome or breathing pore - an opening to the mantle cavity that the snail can open or close at will:

A leaf-veined slug from my garden - the small opening near the "centre line" of the slug is the pneumatostome. Interestingly, leaf-veined slugs don't have lungs, the pneumatostome opens to a series of blind tubes not unlike an insect's respiratory system

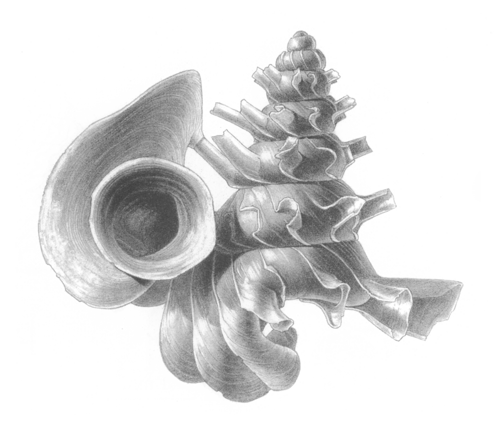

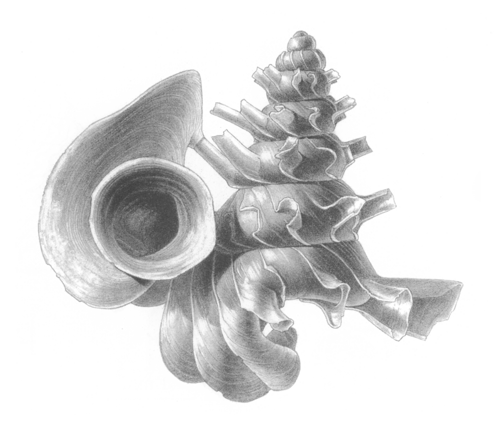

Holotype of

Cytora tuarua B. Marshall and Barker, 2007. Photo is from Te Papa Collectons onlne, and provided under a

CC BY-NC-ND license

Cytora is from the superfamily Cyclophoroidea, a group of snaisl that have indepedantly adapted to life on (relatively) dry land. (

The weirdly un-twisted Opisthostoma is in this post is another cyclophoroid). Cyclophoroids share some stylommatophoran adaptations to life on land, they've lost their gills and replaced them with a heavily vesculalised mantle cavity. Slightly oddly, cyclophoroids also breathe with their kidneys. Or, at least, the nephridium, an organ which does the same job as a vertebrate kidney, includes "vascular spaces" that the snail can use to collect oxygen from the air. Cyclophoroids don't have an organ equivalent to the breathing pore to control the flow of air into the mantle cavity. Instead the mantle cavity is open and air enters by diffusion, or in larger species, as the result of movements of the animals head.

For the most part, the respiratory and excretory systems in cyclophoroids are not as well adapted to life on land as those in their stylommatophoran cousins. For this reason, most cyclophoroids are only active in very humid conditions. In my limited experience, Cytora species are usually found deep in moist leaf litter and soil samples, and I've never seen one crawling about. Nevertheless, some species can survive in drier situations, and these are certainly terrestrial snails.

Local leaf litter samples reveal a third move from the water to land. I don't have nice photo of Georissa purchasi, and I can't find anything else on the web either, so you're stuck with a crumby drawing from my notebook:

I did warn you that it was a crumby drawing. In life

G. purchasi have an orange-red sort of a hue, and you can often see patches of pigment from the animal through the shell.

Georissa species are from the family Hydrocenidae and are quite closely related to a group of predominantly freshwater snails called

nerites. Just like the other lineages discussed, the Hydrocenidae have given up their gills and breathe through a vasculated mantle cavity. Very little is known about the biology of these snails.

G. purchasi is sometimes said to be limited to very wet conditions, but I've collected (inactive) specimens form the back of fern fronds well above ground so it can't be completely allergic to dry .

So, in a handful of leaf litter collected from a Dunedin park you might have cyclophoroids, hydrocenids and stylommatophorans - descendants from three different moves from sea to land. If we look a little more broadly, there are are many more examples of this transition. I've written about the

the helicinids before, then there are terrestrial littorines (perwinkle relatives) some of which have both gills and lungs. Plenty of other pulmonate lineages that have also taken up an entirely terrestrial lifestyle. Because some of these groups have adapted to life on land multiple times, there have probably been more than 10 invasions of the land by snails.

Most of the description of Cyclophoroids here is taken from:

Barker, GM (2001) Gastropods on land: phylogeny, diversity and adaptive morphology In Barker (Ed.),

The biology of terrestrial molluscs (pp 1

—146)

CABI Publishing.

Labels: molluscs, native snails, photos, sci-blogs, science, sunday spinelessness

Posted by David Winter 2:12 PM

|

comments(0)|

Permalink |

Sunday, July 29, 2012

Sunday Spinelessness - Hairy snails

Not the best photo I'll admit, but it records enough detail to see the two things that set

Aeschrodomus apart from most of its relatives in New Zealand. It's tall and hairy. I'm not sure if there is an accepted definition of "hair" when it comes to snail shells, but plenty of different land snails groups have developed processes that extend form the shell. In New Zealand we have the fine bristles of

Suteria ide, the filaments of

Aeschrodomus and the spoon-shaped processes of

Kokopapa (literally "spoon-shell"):

K. unispathulata Photo is from David Roscoe / DoC and is under Crown Copyright

I try very hard to avoid the sloppy thinking that presumes there is an adaptive explanation for every biological observaton, but it's hard to see how these hair-like processes would evolve if they didn't serve a purpose. The larger hairs are presumably made from the same calcium carbonate minerals as the rest of shell, and calcium is a precious resource for snails (so much so that empty shells collected from the field often show signs of having been partially eaten by living snails). In those species with finer projections, the hairs are an extension of the "periostracum", a protein layer that covers snail shells. If we presume that snail hairs come at a cost, in either protein or calcium, what reward are they hairy snails reaping from their investment?

Markus Pfenninger and his colleagues asked just that question by looking at snails from the Northern Hemisphere genus

Trochulus (

doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-59). This genus contains many species that sport very fine and soft hairs. Pfenninger et al.collected ecological data for each species, and used DNA sequences to estimate a the evolutionary relationships between those species. From these data, they were able to infer the common ancestor of modern

Trochulus species was probably hairy, and three separate losses of hairyness can explain all the among-species variation in this trait. Moreover, it appears the loss of hairs in

Trochulus is associated with a switch for wet to dry habitats. Given this finding, Pfenninger's team hypothesised that, in Trochulus at least, hirsute snails might stick to host plants more effectively than their bald brethren. Indeed, in experiments it took more force to dislodge a hairy shell from a wet leaf than non-hairy one.

Pfenninger's study makes a neat case for the maintenance of hairy shells in Trochulus, but I don't think adherence to leaves can explain all the hairy snails we know about. In New Zealand, most snails with shell processes are limited to leaf litter, a habitat that would seem to make adhering to leaves a positive hindrance to getting around. I don't know if we'll ever have a simple answer as to why some of our snails sport these attachments, but

Menno Schilthuizen's work might give us a couple of clues as to why these sorts of shell sculpture arise and stick around. In 2003, Schilthuizen proposed many shell features may arise because those individuals that have them are more likely to procure a mate (or perhaps a desirable mate) (doi:

10.1186/1471-2148-3-13). Although there is quite a lot of evidence for sexual selection in land snails, I don't know of a study testing

Schilthuizen's hypothesis on shell sculpture. On the other hand, Schilthuizen's group has found evidence that elebaroate shell sculpture can arise as a response to predation (doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb00528.x). Opisthostoma land snails from Borneo have extradonary shells, with unwound shapes, ribs and spines:

Opisthostoma mirabile

In Borneo,

Opisthostoma species live alongside a predatory slug that attacks these snails by boring a hole into their shells. The unique shape and ornamentation of Opisthostoma shells appears to have evolved to hinder slug attacks. Even more interestingly, geographically distinct populations of slug appear to attack snails in different ways. This local variation in predator behavior could well be a response to local variation in the shell ornamentation - a so called Red Queen process in which each population evolves rapidly while maintaining more or less the same relative fitness.

There are certainly plenty of snail-eating animals in New Zealand. Several species of Wainuia land snail appear to specialise in eating micro snails, which they scoop up and carry off using a "prehensile tail" (Efford, 1998 [pdf]). It's entirely possible that the relatively small projections that some our snails sport are preforming the same job that those weirdly distorted Opisthostoma shells serve.

Labels: molluscs, native snails, new zealand, sci-blogs, science, sunday spinelessness

Posted by David Winter 8:08 PM

|

comments(0)|

Permalink |

Sunday, July 22, 2012

Sunday Spinelessness - New Zealand microsnails

When I tell people I study snails for a living I get one of two replies. There's either some version of the "joke" that goes "that must be slow-going" or "sounds action packed", or there's "oh, you mean those giant killer ones we saw when we went tramping?". I guess the joke is funny enough, but I want to make it clear that those

giant killer snails from the family Rhytidae, cool as they might be, are not the most interesting land snails in New Zealand.

The local land snail fauna displays a pattern that is quite common for New Zealand animals - we have a very large number of species but those species are drawn from relatively few taxonomic families. Since taxonomic groups reflect the evolutionary history of the species they contain, that pattern most likely arises because New Zealand is (a) quite hard to get to, so few would-be colonists make it here and (b) full of ecological niches and

geographic pockets that can drive the formation of new species. In total, there are are probably about 1200 native land snail species in New Zealand - about ten times the number found in Great Britain, which is approximately the same size. That diversity extends to the finest scales - individual sites in native forest might have as many as 60 species sharing the habitat. New Zealand forests probably have the most diverse land snails assemblages in the world (although tropical ecologists, who generally hold that diversity in terrestrial habitats almost invariably increases as you approach the equator, have argued against this conclusion).

You may now be asking why, if this land snail fauna is so diverse, have you never seen a native snail. Well, you've probably walked past thousands of them without noticing. Most of our native land snail species are from the families Punctidae and Charopidae, groups that are sometimes given the common name "dot snails". Meembers of these families are usually smaller than 5 mm across the shell, and are restricted to native forest and in particular to leaf litter. But in native forests, where there's leaf litter there's snails. Grab a handful of leaves, or pull up a log and you're likely to find a few tiny flat-spired snails going about their business. Hell, down here in Dunedin you can even find charopids living under tree-fuschia in a suburban garden.

Like so many native invertebrates, we know very little about our land snails. Lots of people have dedicated substantial parts of their lives to documenting and describing the diversity of these creatures, but even so we don't have a clear understanding of how the native species relate to each other or to their relatives in the rest of the world, or even where one species starts and another ends. Without such a basic understanding, its very hard to ask evolutionary and ecological questions about these species, so for now we remain largely ignorant of the forces that have created the New Zealand land snail fauna.

For the time being I can tell you that a lot of them are really quite beautiful. Since most people don't have handy access to a microscope to see these critters, I thought I would share a few photos from this largely neglected group over the next few weeks. The 2D photographs, with the relatively fine depth of field, don't quite record the beauty of these 3D shells, but I hope it's at least a window into the diversity of these snails.

Let's start with a snail that is very common in Dunedin parks and forests. This is a species from the genus Cavellia (the strong, sine-shaped ribs being the giveaway) but I won't be able to place it to species until a new review of that genus is published.

This particular shell is from an immature specimen, and is about 2mm across. When flipped, you can see an open umbilicus that lets you see straight through to the apex of the shell.

Labels: molluscs, native snails, photos, sci-blogs, snails, sunday spinelessness

Posted by David Winter 5:30 PM

|

comments(1)|

Permalink |

Sunday, March 25, 2012

Sunday Spinelessness - Looking into the sprial

Next week's post is going to be

really good, but it's also going to be next week. Here's a little taster of a post I didn't leave myself a enough time to write today - a close-up of of the shell of native (

Allodicsus sp.) land snail:

A snail's shell is a complete record of that shell's growth. If you look closely at this photo, you can see that the raised pattern on the shell (the "sculpture") changes. The inner-most coils have "spirals" that run in the same direction as the growth of the shell, while the outer shells have "ribs" that run across it. The point at which this pattern changes marks the end of the snails embryonic growth (called the protoconch) and the beginning of its juvenile and adult growth (the teleoconch). There isn't always a change in sculpture at the point the protoconch gives way to teleoconch, but there is usually some sort of demarcation.

The shape, size and sculpture of snail shells is an important character for the taxonomy of snails - this one is about 0.8 mm wide, which, combined with the sparse spiral pattern it bears fits with the desctiption of

A. kakano.

Check out

Aydin Orstan's post about the protoconch and a few other useful terms for describing shell shapes.

Labels: native snails, sci-blogs, snails, sunday spinelessness

Posted by David Winter 8:11 PM

|

comments(0)|

Permalink |

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Sunday Spinelessness - They're alive!

It would take the most dedicated reader of The Atavism to remember the empty snail shell I wrote about last year. I'll admit even I'd mainly forgotten about myself, but this weekend I went on a little mini-field trip to collect a few samples for a colleague's ongoing project. In planning that trip I did remember the slightly mysterious shells I found last winter, and so decided to head back and see if I could get a few more to send along an an expert who might be able to put a name to them.

Sure enough, I found plenty more empty shells in different states of aging , but deep within the leaf litter I also uncovered one shell that was still playing house to an animal. I couldn't quite be sure there was a healthy animal in the shell when I first picked it up, since the snail was already retracted inside. Thhe easiest way to encourage a sleeping snail out from its shell is to warm in up, so I clasped it in my palm for about a minute and, well, here's the result:

Obviously, having taken the photographs I put this snail back under the nice moist leaf litter from which I'd taken it. Since then I've done a bit of research and I'm fairly confident that I've now identified this population down to genus level. But I've wrong about these things before (most recently by en entire superfamily...) so I'm still going to send the empty shells I collected from the same site to someone who has much more expertise than I do. I'll keep you updated on just exactly what these creatures are.

Labels: Dunedin, environment and ecology, molluscs, native snails, photo, sci-blogs, snails, sunday spinelessness

Posted by David Winter 6:35 PM

|

comments(0)|

Permalink |