Thursday, December 31, 2009

The Origin of Species and the origin of species

2009 was the double celebration for evolutionary biologists, In February we markerd the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin's birth and in November we celberated the 150th anniversary of That Book's publication. Somehow I've managed to go the whole year without dedicating a post to Darwin's ideas about speciation. Which is odd because I've spent quite a lot of thinking about, talking about and even writing about Darwin this year. So here, with about seven hours of 2009 left are a few of my thougts on Darwin and speciation.

Darwin's book was called The Origin of Species but I'm sure that most of the tributes you've read to Darwin and his book this year will have focused on how he proved evolution had happened and provided natural selection as the mechanism required to explain modern organisms in that framework - the fact and the theory of evolution . Missing among the descriptions of the events that shaped Darwin's thinking and the thousands of strands of evidence he wove to form his thesis will have been an answer to the question the title of the books seems to ask - where do new species come from. In fact, there is a prevailing view in evolutionary biology that for all his triumphs Darwin didn't quite understand species and as a result The Origin failed to provide a theory of speciatoin. I don't think it's quite that simple.

To know what someone thinks about speciation you need to know what they think about species.

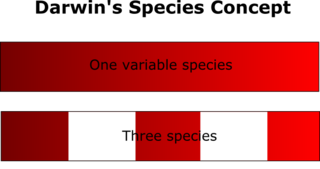

Practically, when a naturalist can unite two forms together by others having intermediate characters, he treats the one as a variety of the other, ranking the most common, but sometimes the one first described, as the species, and the other as the variety. But cases of great difficulty, which I will not here enumerate, sometimes occur in deciding whether or not to rank one form as a variety of another, even when they are closely connected by intermediate links; nor will the commonly-assumed hybrid nature of the intermediate links always remove the difficulty. The Origin, p47Darwin was the sort of person who could develop a world shattering theory, produce a body of data to support it then spent eight years looking at barnacles. Historians of science have spent a lot of ink trying to provide an explanation for "Darwin's delay". It may have been driven in part by an off-hand comment by his correspondent Hooker that only someone who has worked on the systematics of a group could hope to understand the nature of species or might just be a phenomenon all too familiar to modern systematists - a small project that grew out of control. Whatever the cause Darwin's barnacle obsession (on visiting a friend's house his son asked where his friends father "did his barnacles") clearly shaped the way he thought about species. In numerous letters of the time, especially to Hooker, he remarks on the great deal of variation he finds within barnacles of a given species and the great trouble he finds in using that variation to define the limits of species. Partly as a result of his eight years spent dissecting barnacles Darwin came to see the variation within a species as the of the same sort as the variation that exists between species and, importantly, the difference between two varieties of a given species and two distinct species as one of degree not of kind. At the risk of boiling Darwin's ideas down to the sort of diagram you might find in a powerpoint slide here's a pictorial representation.

Hence I look at individual differences, though of small interest to the systematist, as of high importance for us, as being the first step towards such slight varieties as are barely thought worth recording in works on natural history. And I look at varieties which are in any degree more distinct and permanent, as steps leading to more strongly marked and more permanent varieties; and at these latter, as leading to sub-species, and to species. The Origin, p51

It's the fact that Darwin saw no fundamental difference between varieties and species that has lead many, notably Ernst Mayr, to conclude that he didn't understand species and that The Origin was not a speciation book. I read it quite differently. To me it seems Darwin saw the term 'species' as something a systematist could apply to a group of organisms sometime after a process he called divergence (which we would now call speciation) has started to form discontinuities between them.

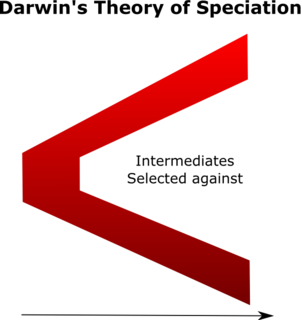

The big question then is what is the process that drives the discontinuities that make for species? The clearest answer to question comes in Chapter 4 of The Origin. Here is one example of Darwin's ideas about the principle of divergence.

It has been experimentally proved, that if a plot of ground be sown with one species of grass, and a similar plot be sown with several distinct genera of grasses, a greater number of plants and a greater weight of dry herbage can be raised in the latter than in the former case. The same has been found to hold good when one variety and several mixed varieties of wheat have been sown on equal spaces of ground. Hence, if any one species of grass were to go on varying, and the varieties were continually selected which differed from each other in the same manner, though in a very slight degree, as do the distinct species and genera of grasses, a greater number of individual plants of this species, including its modified descendants, would succeed in living on the same piece of ground. And we know that each species and each variety of grass is annually sowing almost countless seeds; and is thus striving, as it may be said, to the utmost to increase in number. Consequently, in the course of many thousand generations, the most distinct varieties of any one species of grass would have the best chance of succeeding and of increasing in numbers, and thus of supplanting the less distinct varieties; and varieties, when rendered very distinct from each other, take the rank of species. The Origin, p88In typically prescient fashion Darwin took a proto-ecological view to the experimental evidence that plots sown with multiple plant species where more productive than monocultures. If the the mixed-species plot is doing better than the monoculture it must mean each species is taken advantage of different resources in that plot - what we'd now call distinct ecological niches. But then he took it yet further. What would happen if we let that monoculutre grow on for several generations. We know from his barnacles and from all the examples he listed in the previous chapters of The Origin that variants will arise. A very few of those variants will be able to make use of some of the resources that were previously going untapped. Over many generations natural selection would act - the most specialised forms would produce more seeds and produce more variants while forms intermediate between the ancestral species, not being masters of either niche, would be out competed and driven to extinction. Let this process continue long enough and you'd get first new varietes and finally, since they are just very distinct varietes, new species. Darwin provides his own diagram (the only one in the book) to describe this process and its phylogenetic implications but that is, in my supervisor's words, "a rattly looking thing" so here's one from me.

I find it very hard to marry the received wisdom that Darwin failed to understand the nature of species and provided on theory of speciation with the arguments Darwin presented in The Origin. When his species concept is viewed (as I think all such concepts should be) as a diagnostic tool rather than an essential definition then his is as good as any other. His theory of speciation as presented doesn't hold up to our modern knowledge of genetics but the underlying process, selection driving ecological specialisation, forms one half of our modern models of speciation that don't involve geographical isolation and those that involve secondary contact between incipient species.

Labels: Darwin, evolution, history of science, might interest someone, sci-blogs, science, speciation

2 Comments:

I might try and go one better and write some posts like this but without the typos!