Sunday, October 31, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - Gymnast

It's been a very busy weekend after a very busy week down here, so I'll let a couple of photos do most of the talking today. A stick insect nymph skillfully traversing agapanthus leaves in order to escape a photographer:

And a detail, with the chewing-mouthparts

That's it for today, I'll be sure to have something mode detailed for you next week.

Labels: environment and ecology, phasmidae, photos, sci-blogs, stick insect, sunday spinelessness

Sunday, October 24, 2010

A year of Sundays

It's been as close to a year as we are going to get since I posted the first Sunday Spinelessness. I wasn't quite sure that I would be able to keep up the weekly schedule when I started the series, but I've managed it minus breaks over Christmas and for my trip to the USA and Canada (there are occasionally times I try and stay away from computers). Part of the reason I called the first post Sunday Spinelessness was to guilt myself into writing at least one post a week, and as I've moved more and more into writing up my own research over this year these Sunday posts have been a really welcome break (and a good writing excercise at that). As you can tell, I've been in a slightly reflective mood thinking about this post, and when I get reflective I like to look at some data.

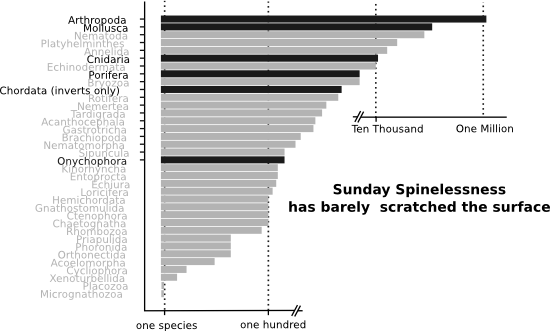

Like, how representative has these Sunday Spinelessness posts been? The phylum is the highest level of classification within a taxonomic kingdom, animals placed in different phyla represent fundamentally different designs for life and in the order of 600 million years of independent evolution. In day to day life we probably only aware of a few phyla, vertebrates make up the bulk of Chordata, insects crustaceans and spiders are all arthopods, snails and clams are molluscs and earth worms are annelids. Depending on who you ask, and when you ask them, there are 36 animal phyla ( the confusion mainly caused by strange animals with almost no useful characters for taxonomists to look at). So, how may have been represented here:

Click above to see a larger version, note the x-axis is on a log-scale and number of species is number currently described

I knew I mainly wrote about arthropds, but I've only written about about 6 of the 36 animal phyla? It looks like I have a lot more work to do. Some of the phyla I've so far neglected are fascinating creatures;there are probably hundreds of thousands more nematode species that currently described and one of them is an important model organism in cell biology, echinoderms share some fundamental aspects of their development with vertebarates but end up being radically different (with five-fold symetry rather than our "down the middle" two fold symmetry), brachiapods look a lot like bivalve molluscs (clams and oysters and the like) and were once many times more common than their look-alikes but are few and far between now, tardigrades might just be the coolest animals on (or indeed off) earth. Even more excitingly for me, there are phyla in there I know almost nothing about. Apparently, Rhombozoa means "lozenge animal" and this phylum is restricted to parsitising the renal gland of squids and octopusses, and phoronids are worm-shaped but have a gut that loops back towards the mouth, and so on it goes.

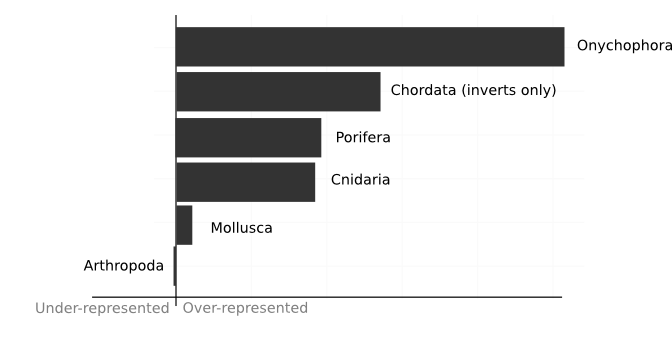

Ok, so I haven't really touched on the true diversity of life without a backbone yet. What about the numbers, about three quarters of these posts have been about arthropods which represents the avaliability of photographic subjects in my bakcyard but must over-represent these creatures as a whole? I came up with an index to display how representative a phylum's post count is here. You should probably just skip to the graph which is pretty self-explanatory, but if you wanted to know the formula is

representation = log ( (speciesphylum / speciestotal) / (postsphylum / poststotal) )

And the graph:

So, arthropod species actually make up even more of the biological world than they do posts here (and just one post about peripatus is enough to make Onychophora the most overrepresented group of all). I also have to feel a little shame as a dilettante malacologist that I haven't spoken nearly enough about the molluscs thus far. There is another post on the way with those leaf veined slugs which should help tip the balance though.

Well that's about it. A quick look at the data tells me I'll have no trouble finding subjects for future Sunday Spinelessness posts and I can be a little less concerned about featuring so many arthropods!

Labels: blog blogging, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness

Sunday, October 17, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - Blog them and they will come

I think our backyard's bugs are on to the fact that they are sometimes the subject of posts here at The Atavism. Take last week, it's been months since I took those photos of a leaf veined slug and I hadn't seen another since. But then, wandering home in the dark this week I spotted this eerie outline through a black-lit leaf.

The eerie outline belonged to another leaf veined slug. To help me with another project I might talk about here at some stage, I promptly chucked the slug in a bucket with a nights worth of leaves graze on. Which also gave me a chance to photograph the slug in some nicer light.

Before it made it was back to a nice dark retreat somewhere in a native flax (Phormium) bush:

But the one that really spooked me were those little green spiders I really ought to have sent away to someone who knows their spiders. As soon as I'd submitted that post I stuck my head into that horrid agapanthus and was amazed to see two new green spiders. Over the months since then I've been keeping an eye on them, and there are now about 15 of them eating aphids, spinning retreats and generally hanging out in the sun.

So, it was time for me make a sustainable harvest. On Friday afternoon I grabbed a paintbrush, a few vials of 95% ethanol and some waterproof paper so I could catch, preserve, and document a few of these spiders and send them to Phil Sirvid at Te Papa who is interested in working out which name these guys should have which will in turn hopefully make the observations I continue to make of this thriving little population a bit more useful.

Labels: environment and ecology, photos, sci-blogs, spiders, sunday spinelessness

Thursday, October 14, 2010

Ka Pai Kakariki

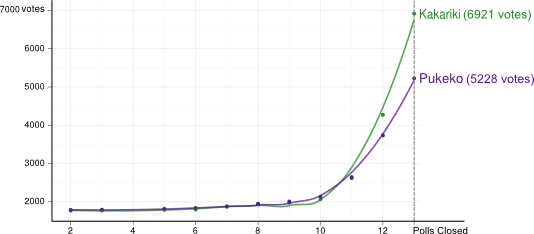

New Zealand has spoken, the kākāriki is our newest Bird of the Year. It took a late surge to push the slender parrot past the other main contender for the prize, the pukeko, but in the end the kākāriki won a clear majority and it's time for the nation to celebrate these endangered birds.

New Zealanders are rightly proud about some of the weirder creatures that call our islands home. Our native wrens, frogs, tuatara, large parrots and kiwi are all examples of ancient lineages found in New Zealand and nowhere else in the world. These species, and our geological origins, have formed part of New Zealand's creation myth - a country that went its own way 85 million years ago and has been doing its own thing ever since. The kākāriki don't fit in that narrative. Instead, theses parrots connect New Zealand's biota to the Pacfic and serve to highlight the way the recent geological and climatic history of our islands has shaped the creatures we share them with.

When we say kākāriki we are actually talking about three species of small parrot, each native to New Zealand. There had been considerable debate among ornithologists about whether the different forms, which are most easily differentiated by the colour of a patch of feathers on their forehead, really represent different species rather than variants of a single species. In 2001 Wee Ming Boon, then a PhD student at Victoria University in Wellington provided the answer. Molecular data showed that each of these forms are distinct from each other.

When Europeans first arrived in New Zealand all the kākāriki species were relatively common in beech forests. So much so that when the beech failed to set enough seed for the parrot populations they would invade the settler's farms and orchids. Robert Fulton, speaking to the members of the Otago Insitute in 1907, noted how the birds which had been "shot in their thousands" only thirty years before had all but disappeared. (The Otago Witness also recorded Dr Fulton's sentiment that the way Kererū were slaughtered in the province put Otago-ites on "the same level as the Spanish and the Mexicans") . Today all three species are endangered, deforestation and the introduction of mammalian predators like the stoat being a much more to blame than early orchardists. The yellow fronted species is still relatively widespread, whereas the red fronted is extinct on the mainland and the orange fronted is restricted to few small pockets of beech forest in the South Island and there may be as few as 50 birds left.

All three species are in the genus Cyanoramphus, which has representatives stretching from Raiatea in the Society Islands all the way down to Macquarie Island in the sub-antarctic. The same sort of molecular evidence that was sued to establish species status for the various kākāriki can be used to establish relationships between them and their Pacific cousins. The New Zealand species are most closely related to a species from New Caledonia. Using a molecular clock analysis, Boon and colleagues could show that modern populations of kākāriki on New Zealand and the Chatham Islands descend from a single invasion of our country from the Pacific, most likely from New Caledonia, within the last five hundred thousand years. Interestingly, the three New Zealand species split even more recently than that. It seems seems populations of kakariki become isolated within pockets of beech forests that survived the last ice age. Seperated in this way, populations would become become independently evolving lineages, which in turn can come species.

It might seem that recent arrivals like the kākāriki aren't quite as uniquely New Zealand a group of birds as those ancient and odd birds like the kakapo and the kiwi. But, as we've been able to apply molecular tools to more and more of the plants and animals we share our islands with it's become increasing clear that recent arrivals far out number the old timers. In fact, in many ways the kākāriki is a perfect example of the way life has evolved in New Zealand . It's been here for only a short while, but in that time the turbulent geological and climatic history has shaped these birds in a unique way. So, apart from being very handsome parrots indeed, the kākāriki are worthy holders of the title of Bird of the Year. Now let's just make sure we get to keep some of these birds in our forests!

Labels: bird of the year, evolution, kakriki, new zealand, sci-blogs

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

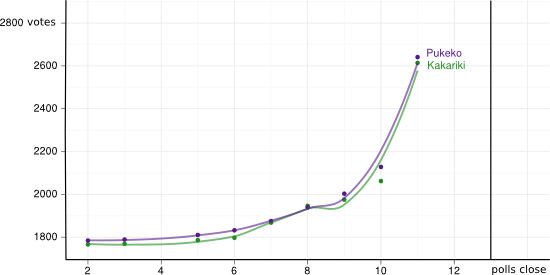

Tight at the top as polls set to close

By DAVID WINTER 12th October

With two days of voting left the pukeko is maintaining a slender lead over the kakariki in its race to become 2010's bird of the year. According to voting data made available to The Atavism last night, the pukeko was a little over 50 votes in front of its psittacine rival. The two birds cleared away from the field early in voting, but have been locked in a tight struggle since then. The increased interest caused by their head-to-head battle has lead to a record 13 000 votes being cast, with almost half of them falling to one of the top two candidates.

Labels: bird of the year, environment and ecology, sci-blogs

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - A leaf veined slug

You see some pretty impressive photographs in bug-blogosphere. People like Alex Wild, Adrian Thysse, Ted MacRae and Mike Bok use impressive gear, and much more impressive skill, to serve up wonderful shots of the smaller inhabitants of the natural world. Not so much here. Photographing the subjects for these posts greatly increases the joy that I get from observing their lives, but I don't claim to have any real skill and, except for that one time, the photography around here is all point-and-shoot. But I've never shared anything quite as amatuer as the photos I'm about to show you.

Earlier this year I bought Ray and Lyn Foresters very cool book on New Zealand spiders, and read about the genus Celaenia, the members of which spend their evenings dangling from a thread impersonating a female moth (in both look and scent) in the hope of making a meal of a male moth. I thought I should spend at least part of one of my evenings seeing if I could find any Celaenia in our garden. And so it was that I found myself out in the cold shining a flashlight into bush after bush looking for spiders and discovering only a bright yellow slug:

At first glance I presumed it was one of those lettuce destroying introduced species, perhaps Limax flavus, but most of the slugs introduced to New Zealand have cylindrical bodies and pronounced mantles (the organ that would have made their ancestor's shells and ends up looking a bit like a saddle on the front of the slug) and this one is flat and has no obvious mantle. In fact, this is native slug, from a pretty cool family. So, I just had to try and photograph it. There is no way the flash on my camera can illuminate a subject less than a few metres away, and no way its lens is going to record any details in a subject more than a few metres away. So, i stood outside, in the dark, with one hand pointing a flashlight at a slug and the other holding my camera away from me, with neck strap held taught in the hope this pose would stabilise the camera enough to get some sort of shot to share with you. It's really a miracle I got anything from about ten minutes of that farcical photo-shoot, but here you go:

Now you can make out the patterns that give these slugs their common name - the leaf veined slugs ( I have no idea what the taxonomic name for this family, Athoracophoridae, refers to). This species, probably Athoracophorus bitentaculatus doesn't have the prominent colouring that some if its relatives do, but you can still see the "veins" as furrows running through the rougher parts of the slug's skin. We have about thirty species of of leaf veined slugs in New Zealand and, like most of our land-living molluscs, we don't know an awful lot about them. Massey University's "soil bugs" site (which is pretty awesome by the way) has a gallery of leaf-veined slugs, which includes surely the cutest mollusc you'll see today.

Lately I've been spending one day each week in the lab dissecting the landsnails that are the subject of my PhD. The most common question I get from labmates and anyone that asks what I've been up to lately is "how do you know which bit is which". I understand the sentiment, because looking back on my notes I clearly had no idea when I started, but I think between Aydin Orstan's photos and a side-by-side comparison of this slug with this diagram of its internal anatomy you can at least get a feel for the lay of the land.

Labels: environment and ecology, leaf veined slugs, photos, sci-blogs, snails

Thursday, October 7, 2010

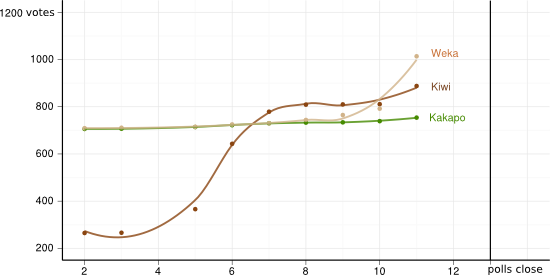

A two bird race

You are running out of time to cast the most important you will have this year - who will run your community be voted Bird of the Year for 2010? This year I stepped up an offered my services as campaign manager for the the bellbird, and frankly i've done a terrible job. With nearly 9 000 votes cast the korimako has 51, or about 0.05% of the electorate's support. I'm sure this at least parially because Forest and Bird didn't include my completely unoriginal campaign logo in their post:

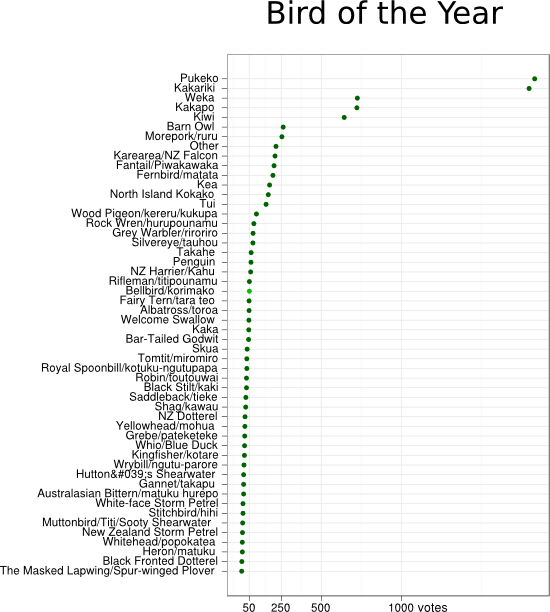

There, that got to be worth a vote or two right? I think it's all a bit late for the bellbird this year, because the poll has already become a two bird race. These are the standings scraped from the Forest and Bird site last night:

So it's a head to head battle between the Pukeko; a multinational entity which shills for one of the country's worst polluters, and the Kākāriki; a bird whose very name means green. Obviously, the bellbrid campaign still values and wants your vote, but if you can't make the korimako your bird of year, then we urge you think green!

Labels: bellbird, kakriki, pukeko, sci-blogs, science and society

Sunday, October 3, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - How the aphid got its blush

Once upon a time, a green aphid lived on a plant somewhere. Like most of her kind, this particular green aphid didn't have wings so her whole life was going to be spent on this one plant, sucking away at the plant's sweet sap. You might be quite jealous of this aphid's life, since for an aphid a plant's sap really is an Exceptional Confection and she spends her time doing nothing but drinking it. But her life was harder than you might imagine, at the moment she was pregnant and her one goal in life was to make sure her babies would have a safe life here on this plant. This was long before gardeners came in to the world with pyrethrum and soap spray, but she had plenty of other enemies that could make life very hard for her and her babies. The scariest of all of the aphid's enemies were the wasps. The wasps would fly from plant to plant, smelling the air with their manically twitching antennae and searching for little green bodies with their eyes. This was very bad for the aphids, because theses wasps, just like the Ichneumon you already know about, would like nothing better than to use an aphid's body as an incubator for the their own babies.

And here comes the magic bit of our story. Our aphid wasn't feeling very well, she was infected by some fungus or other which was spreading through her body. You know that when you feel ill that you get hotter and you might swell up, and that's because you body is fighting back against your illness. The aphid's body was fighting back too, breaking up the fungus cells and stopping their spread. The aphid didn't know that her body was fighting fungi, all she knew was that she was starting to feel better, but something amazing was happening inside here. All those broken up fungal cells in her body had left their genes floating around, and one of those genes found its way into one of the aphid's babies.

A few weeks later the aphid was feeling much better, and it was time for her to give birth to her babies. Can you imagine her surprise when one of her babies wasn't green, like every other aphid that had ever existed until now, but was bright pink! She was staggered, but she always called her pink baby her Best Beloved and she never cared for her less than her green babies. And when the wasps came, with their twitching antennae and their giant scanning eyes, they always missed the pink bodied aphid. So the pink bodied aphid grew up and had pink bodied babies, and they got missed by the twitching, scanning wasps too so they had even more babies. So now, all these years after our aphid lived on her plant somewhere every pink aphid in the world can thank her, and her fungal infection, for their lovely colour.

***

No, I can't write the whole thing as a Just So Story, and I certainly can't write the poem that should finish it. But I do want to talk a little more about these guys:

I guess for most people a rose covered in little pink aphids is one of the less welcome signs of spring. I'd like to see the rose do well and produce lots of flowers, but I was also happy to see such a wonderful illustration for one of the most interesting pieces of evolutionary genetics to be published this year:

Lots of aphid species come in pink and green flavours, but just how the pink ones keep up their colouration has been a bit of a mystery. It's been known for a long time that the pink pigments are caratenoids, the same family of chemicals that make carrots orange and tomatoes red. These chemicals are important parts of lots of biochemical pathways, but animals can't make their own and have to rely on what they can eat. Except for aphids. Aphid caratenoids are slighltly different than those of their host plants, so they must be making their own but just how they can do that had been a mystery until this year. Mike Bok at Arthropoda and Ed Yong at Not Exactly Rocket Science covered the story when it broke, so here's the short version:

The pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum, has become something on an unlikely model organism recently, and has even had its genome sequenced. Nancy Moran and Tyler Jarvick realised that the release of the pea aphid genome data was their chance to work out how the aphid got its caratenoids. They searched for genes similar to those that make up the caratenoid production pathway in plants, fungi and bacteria in the aphid genome and found some. Even more excitingly, there were able to relate the aphid genes to their relatives across the biological world and conclude that the genes of the aphid catatenoid pathway are most closley related to fungal genes - the aphids got their pink colouration from a fungus genome.

The transfer of genes from one organism to another outside of the traditional parent-offspring relationship is called horizontal gene transfer. In recent years it's become increasingly obvious that single celled organisms have been swapping genes in this way since life began, but the aphid case is among the first times horizontal gene transfer has been confirmed in animals. I should say, my little tale up there is a just so story in more ways that one. We really don't know how an aphid acquired fungal genes. Perhaps it was an infective fungus broken down an immune response, maybe it was raw RNA reverse transcribed into the aphid's genome or maybe there was a bacterial conduit. Wild aphid populations have a lot of symbiotic bacteria which can help them adapt to particular host plants and environments, perhaps in the past they had another that used fungal genes to change the aphid's colour and those genes have since migrated to the aphid's own genome.

Moran, N., & Jarvik, T. (2010). Lateral Transfer of Genes from Fungi Underlies Carotenoid Production in Aphids Science, 328 (5978), 624-627 DOI: 10.1126/science.1187113

Labels: aphids, bugs, environment and ecology, photos, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness