Sunday, November 28, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - Wolf spiders

Lately I've been trying to reclaim a little of our garden from the weeds that claimed it for themselves over the winter. My dedication to weeding is not absolute, and instead of diligently tugging each weed out seperately I almost end up plucking the big ones then driving my hander und the soil to disturb the roots of the smaller ones. That method is bad news for the wolf spiders that live in and around the bark we use as mulch in the garden.

Wolf spiders are reasonably large hunting spiders, and at this time you can see one of their defining characteristics. Female wolf spiders carry their egg sacs around with them. I'm not sure how many times I've knocked over a piece of bark and seen a few legs and an abdomen ducking for cover:

But I've only managed to start a fight once. Last weekend I upset a piece of bark with two wolf spiders hiding under it, and in the commotion that followed one of them lost her egg sac. For the next five or so minutes, a fierce fight broke out between the two spiders. Guilty as I was about having started this fight, I managed to record a little of it:

Labels: arachnophilia, environment and ecology, photos, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness, wolf spiders

Sunday, November 21, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - Another Angle

I don't claim to be a great photographer, but I do feel a little smug about today's photo. But it's not even the photo itself that gives me an misplaced sense of satisfacton.

Let me explain, the photo was taken inside the rain forest exhibit at the Vancouver Aquarium. Than aquarium is a big tourist attraction, and there were tonnes of people moving through the various displays the day I was there. The crowd in the rain forest in particular was moving pretty slowly, as people tried to capture the the photos of the ibises, marmosets, turtles and other charismatic mega fauna. There were also Costa Rican butterflies in the rain forest enclosure, and you won't be surprised to learn I was more interested in photographing those than anything else (though I did photograph a few vertebrates that day). A few other photographers showed a little interest in the butterflies, mostly getting the standard butterfly portrait, a top down shot of the insect with its wings open:

There's nothing wrong with the standard butterfly portrait, but I thought the way this guy was set up on his branch can an opportunity for a slightly more interesting shot. So, being far to far from home to feel the least bit embarrassed, I braced by myself by swinging one arm around the butterflies branch, balanced the camera in front of the subject and (with my feet just dangling above the ground) took some photos:

I was quite chuffed with the result, but I was even more pleased when I looked back a few minutes later and saw the photographers who, having foresaken the ibis and the marmoset, had lined up to photograph the same butterfly. Score one for the spineless!

(If you were wondering, I'm pretty sure the butterfly is the Nymphalid Siproeta stelenes)

Labels: butterfly, environment and ecology, Nymphalidae, photos, sci-blogs, Vancouver

Friday, November 19, 2010

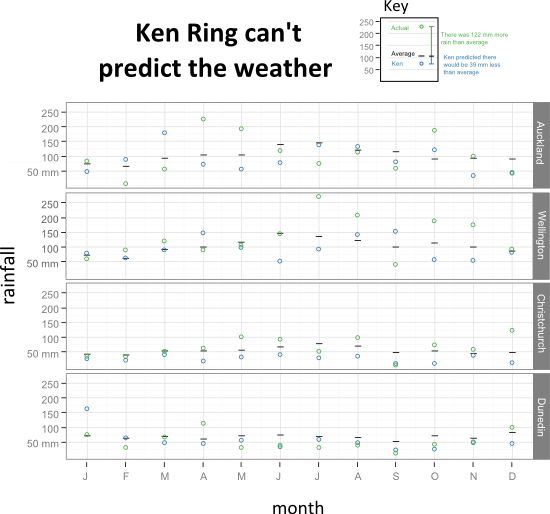

Ken Ring can't predict the weather

It's that time of year for academics in New Zealand. As soon as undergrad teaching finishes every department, organisation and society on campus decides to schedule some sort of meeting,conference or symposium - since everyone will have so much spare time. Between the three talks I'm going to end up giving this month, and the tonne of work I have to get done between them, I don't have much time to write here. So, partly inspired by people talking abut their months-old posts in Grant's piece on the length of time it can take to put a blog post together, I've decided to dive in The Atavism's "draft" folder and resurrect a few half-written posts. This one took about two months to write, and though I never quite got the copy right I do rather like the graph.

Ken Ring was on National Radio a couple of months ago, blathering on about his method of weather prediction. Ring thinks he can provide a forecast for any future date by looking at weather map that's about 18 years out of date That's how long it takes for the earth, the moon and the sun to cycle into the same relative positions in their orbits, and Ring thinks it's the moon that drives weather down here on earth. The 18 year old weather map will tell him what the atmosphere was doing last time everything lined up this way, and that will be enough to predict the next event. You probably agree that Ring's methods sound like lunacy, but Ring continually claimed in his time on air that his method had an 85 % accuracy rate. Reading Ring's website, you can see he is pretty generous when he estimates his own accuracy, like the Texas sharpshooter who shoots the side of a barn then paints a target around the bullet hole to show his prowess with a shooting iron, Ring uses any vaguely similar weather event to prop up the accuracy of his predictions. My particular favourite from that page is his prediction for 100 mm or rain in New South Wales, which was accurate, it's just that it arrived further West, two days later and was a only 20mm.

So, we shouldn't take Ring's self confidence too seriously and his method, which involves tricky maths and obscure terminology, is a prefect example of cargo cult science. But we don't have to stop there, Ring makes specific predictions that we can test. Just as the worst thing you can say about homeopathy is not that it's impossible for those dilutions to effect the human body, but that homeopathy has been shown to do nothing; the worst thing you could say about Ring's weather forecasting methods is that they don't work. I went digging for some of Ring's old claims and was thrilled to see that my Sciblogs stablemate Gareth Renowden has already done all the hard work for me! Apparently Gareth was been dealing with crazy people and weather even before he launched Hot Topic, and back in 2006 he got his hands on on Ring's predictions for rainfall and sunshine hours in each of the major centres. Gareth compared those predictions to the actual values and to the long term average kept by NIWA.

There's a bunch of stuff that can be done with that data (which Gareth kindly made available for anyone to download), but the most important thing (and this holds for almost any statistical analysis) is to take a look at it. Here's what I came up with for the rainfall data using the rather wonderful ggplot2 and inkscape :

You can click on the graphic above to get a bigger version. In these graphs the long term average for each observation is the black line, Ring's predictions if the blue circle and the actual rainfall for that month in that city is the green circle.

You can click on the graphic above to get a bigger version. In these graphs the long term average for each observation is the black line, Ring's predictions if the blue circle and the actual rainfall for that month in that city is the green circle.

Now, let's test the accuracy of Ring's predictions, but against what? Statistical tests often compare a set of results to what you might expect to get "by chance" but that's not very helpful in this case. For one, it's not clear what the range of possible values should be, and second, comparing the forecasts to numbers picked at random ignores the seasonal effects everyone knows contribute to weather. You don't have to know the position of the moon 18 years ago to know that Auckland is more rainy in July than January. Instead, let's compare Ring's forecasts to the easiest forecast you could ever make - just saying rainfall for a given region in a given month would match the long-term average. If there was anything to Ring's methods he should be able to do better than that. He didn't, on average Ring's prediction was 52.5 mm out from the actual rainfall where as "predicting" the average would have been 37.25 mm out.The long-term average was a better predictor, averaging 15.15 mm closer to the actual rainfall with a confidence interval spanning from -0.4 and 31 mm. We can't (quite) say from that data that Ring's forecasts have less predictive power than the long term average, but there is absolutely no evidence they're any better.

Let's lower the bar a little and forget about how close to the true value Ring's predictions came. Was he at least able to get on the right side of the average? If he predicted a drier August than average was the real value likely to indeed be direr? In this case, if you just tossed a coin 48 times, calling heads drier and tails wetter, you'd expect to be right about half the time. And would have done better than Ring. His prediction was only on the right side of the average 17 times in 48 attempts, about 35% accuracy and significantly worse that you would expect to get from tossing a coin (if you're one of those p-value fetishists p, in this case, is equal to about 0.03) .

So Ken Ring can't predict the weather. That probably doesn't surprise anyone reading my blog or at sciblogs.I wish it surprised me that the uselessness of Ring's forecasts is no barrier to him being taken seriously, selling books and appearing on radio and in newspapers. The host of the show that started by little investigation evidently took some flack for having Ring on (it was a National Radio after all) and his defense amounted to "well, we just let these people talk and you can decide what you think about it". That seems impossibly weak to me, surely the least we should do is ask people who make outrageous claims to show what evidence they have to support those claims. I'm pretty satisfied there is nothing in astrological weather forecasting, but if advocates of the method really want to put it to the test it would be easy. Get someone to provide a year's worth of old weather maps but let only half of them be of the right vintage for their method (about 18 years in Ring's case) and see if the forecasts from the supposedly predictive weather maps are better than the ones from weather maps chosen at random. How likely do you think it is that test will be run?

Labels: pretty data, sci-blogs, science and society, skepticism

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - My own ID challenge

Some of the cooler kids in bug-blog world post identification challenges from time to time (1,2,3). I seldom get very far on those challenges, in fact, they usually serve only to make me wonder if there is any obscure insect group Ted McRae can't ID from a single photo.This month I've had my own little ID challenge sitting out in the garden, the Pittosporum is infested with these:

Sadly, I have to admit I didn't even recognise these guys as animals on the first take (the greatest taxonomy fail ever?). Just passing by the bush it's easy to mistake the dark patches for some sort of of blemish within the leaves themselves. But blemishs don't tend to move, and they're not usually so unerringly associated with winged bugs:

The 'blemishes' must actually be flattened sap-sucking nymphs on their way to becoming the adults on the left. "Flattened sap-sucking nymphs" sounds a lot like scale insects. Scales are a diverse group of true bugs known to gardners because one group, the mealy bugs, are a fairly common plant pest. In New Zealand, scale insects are of immense ecological importance. Ultracoelostoma scales live within the bark of Southern Beech (Nothofagus spp.) trees. These scales act like little siphons, they stick their mouths into the phloem (the sap) of the tree while the other end of their digestive tract extends out from the tree's trunk on a long waxy filament. The excreted sap, which is still very energy-rich, forms in a droplet at the end of the anal filament. If the sugary droplet stayed at the end of the filament for too long it might harden, and prevent the flow or more sap into the scale insect's body. There isn't much risk of that happening though, the 'honeydew' provided by scale insects is a valuable food source in beech forests (which are usually short on fruit and flowers). Nectar eating birds, including the tui, bellbird and kaka, visit trees every few minutes to drink the scale insect's honeydew.

Sadly, these days introduced yellow jacket wasps are probably even more frequent visitors to scale insects. A healthy beech forest can support 10 000 of these social wasps per hectare (about ten times the density they reach in the Northern Hemisphere), that's a big enough army of wasps to take the honeydew resource away native birds and to go on and kill thousands of native invertebrates. (Landcare Research have page explaining the beech scale insect and the impact of wasps)

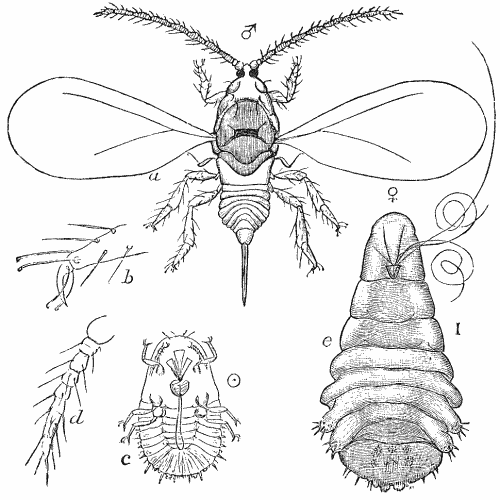

But that's all an aside, because the nymphs on my Pittosporum can't be scales. Scales are one of the few animals I can think of in which one sex doesn't develop as far as the other. The long maintaince of juvinile characters in adult organisms is called neoteny (the axolotl, a salamander that never metamorphoses but still reproduces, is probaly the most familar example of this phenomenom). In scale insects the adult female looks for all the world like those flat-bodied nymphs, while the adult is a two-winged bug (which looks... like nothing else really). There is a diagram of the adult scales in Project Gutenberg's version of The Life Story of Insects:

I have reason to belive that the adult females on our Pittosporum look aobut the same as the adult males:

Actually, the fact these guys are living on the Pittosporum should have been the give away to what they are. Plant sucking insects often become highly specialized, with species adapting to a particular host plant. These insects are the most common Pittosporum pest species Trioza vitreoradiata, the Pittosporum pysllid*. Apart from the fact the psyllids are related to aphids and scales and few other primative true bugs I can't tell you a lot more about them. Apparently they make good eating, I've seen worker ants and this fly abscond with nymphs:

I've also noticed one other, quite endearing habit. Almost any time one of the adults moves they do so by pointing their head down and their butt up and wiggling. Here, for the first time, is the psyllid boogie recorded for your viewing pleasure (this particular performance was delivered on my outstretched hand, which this psyllid thought would be a safe place to escape to when it got sick of having a camera in its face):

*This isn't a particularly accurate name. Pysllid is a name describing members of the family Psyllidae, but most recent taxonomies have placed Trioza in a separate family. Both are still in the superfamily Psylloidea, so I guess they should be called psylloids, which sounds even more sci-fi then there usual name.

Labels: bugs, environment and ecology, photos, psyllids, scale insects, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

Flash Fiction

A friend of mine send me a link to New Scientist's Flash Fiction competition. The idea is pretty simple, write a super-short (350 words) story on the way the world might have been if some now disproved scientific theory turned out to be true. Get an entry in and it might be published in New Scientist and, much more excitingly, Neill-Freaking-Gaiman might read whatever crazy idea you came up with.

Three hundred and fifty words is about a prefect word count for my schedule at the moment (although it does take quite a long time to write something that short) so I've been working on a couple of ideas. You can only submit one story to the competition, so here's the one that I deemed too silly to send in. (There are bonus points for anyone who can explain why this wouldn't work even if recapitulation theory did turn out to be true)

Researchers Recreate Human Ancestors

- Bipedalism nothing new

- First animals sponge-like

- New tools create ethical dilemmas

An historic series of publications presented in PLoS Biology today detail how scientists have recreated stages of our species’ evolutionary history for the first time. Researchers took advantage of new technologies and the fact organisms recapitulate their evolutionary history during their embryological development. By arresting development of an embryo at an early stage and “knocking out” genes inferred to have arisen at different times in humanity’s evolution researchers recovered the developmental program of two human ancestors.

Etienne Meckle, the head of the Human Ancestor Project (HAP), expressed his amazement at the achievement.

“ 150 years ago - when Ernst Haeckel presented the modern version of recapitulation theory - Darwin’s ideas of evolution were new, we didn’t know what a gene was and we didn’t understand embryology at all. Now, two human lifetimes after his work we’ve used his theory to recreate two of our ancestors”

The creatures so far created by the HAP had been separated by 600 million years. By halting development of a human embryo after four days, and removing the effects of all genes not shared by all animals, scientists created a simple filter-feeding animal. This early animal is similar to a modern sponge, and supports the long held theory that the first animals were sponge-like.

The second of the team’s creation is bound to prove more controversial. Merca is a 3 foot tall ape, thought to similar to the last shared common ancestor of modern apes and not seen on earth for 32 million years. She walks on two feet, a trait once thought to be unique to modern humans.

Scientific controversy aside these results have fueled a wider ethical debate, summarized by a comment by BioEthaciser121 on the PloS Biology website:

“Science has delivered us the ability to bring intelligent animals into a world they can’t possibly be prepared for. Society now needs to decide if we want to do that.”

Both recreated ancestors are on display at the National Zoo in Washington, DC.

Labels: evolution, fiction, Human evolution, sci-blogs

Sunday, November 7, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - Now tell me spiders can't be cute

Today is going to have to be another photo-centered Sunday Spinelessness, after I managed to let most of my Sunday slip through my fingers between sleeping in and catching up on work. Still, this is a particularly cute photo so perhaps a shortage of words from me is not great loss:

The subject of this photo, a jumping spider, might look like it's staring away into the middle-distance. In fact, it's calculating. Most spiders are very shy and retiring, and at the first disturbance of their hideout they'll retreat to some dark corner and hide there until the coast is clear. Not so the jumping spiders, disturb a jumping spider and, likely as not, it will walk towards you and start to consider you as potential meal. They really remind me of puppies that are yet to learn they are much smaller than the big dogs, and any fight they pick with them isn't going to end well. This jumping spider seemed to think the camera wasn't much of a threat, so went after yet bigger game an jumped on to me:

After a while spent patrolling the knuckles and the base of my left hand it became clear nothing very much was going on, so the jumping spider lived up to its name an vaulted off in search of something more interesting while I cursed my inability to take a decent shot of it one handed.

Labels: arachnophilia, jumping spiders, photos, sunday spinelessness