Sunday, May 30, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - The Wasp That Did For Darwin's Faith?

I own that I cannot see as plainly as others do, and as I should wish to do, evidence of design and beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae ...

Here's one the Ichneumonidae, the family of wasps that Darwin couldn't fit into a world with a loving god.

What could Darwin find so abhorrent about such a fine looking creature? It was their unique approach to parenting the put Darwin off. Ichneumon are diligent parents, to make sure their offspring have all the food they could ever need the wasps lay their eggs in the bodies of other insects. The larva develops within the host insect, carefully keeping the doomed creature alive as it eats its way through first its fat stores then its non-essential organs. Finally, with the larvae almost fully grown it turns its attention to the host's essential organs before it eats its way through the skin. The ichneumon life-cycle was the inspiration for the chest bursting aliens in the Alien movies.

The quote that started this post is often presented as an observation unique to Darwin, or even as a sort of epiphany that did for Darwin's faith. In fact, Darwin was repeating what had become an old saw by the time he wrote it. The ichneumon lifecycle was widely discussed by Victorian naturalists and theologians. At that time there was a great deal of interest in an idea called natural theology, which amounted to learning about god by studying his creation. But some pats of nature don't seem to reveal a beneficent god. The natural theologians managed to convince themselves that the lion hadn't yet laid down with the lamb because predators saved their prey a worse fate, but the idea of ichhneumon larvae rasping away at their hosts from the inside out proved a greater challenge.

Stephen Jay Gould wrote an essay on the problem of the ichneumon which lists some of the ways natural theologians tried to deal with it. William Kirby, the great entomologists who also happened to be a reactor, emphasized the great dedication of the wasp to her offspring and praised the larvae's sustainable approach to eating their hosts while saving mroe live tissue for later. For modern readers it seems very odd to be describing wasps as virtuous. By and large we've come to realise that nature doesn't provide moral lessons, but we haven't quite given up the naturalistic fallacy that drove the natural theologians. How many times have you hear peddlers of snake oil claim their product was safe "because it's natural"? Or people object to genetic engineering or vaccines because they are unnatural?

We even still look on nature as a source for morality, proponents on either side of the debate for gay rights swap statistics on how common homosexuality is among other animals - as if the sex lives of bonobos or prairie voles had anything to do with human rights. If there is a lesson to learn from the gruesome life-cycle of the Ichneumonidae it's that nature just is, and we need to turn elsewhere for moral lessons.

Hold on, these posts are meant to be about celebrating weird bugs. Let's end with the great David Attinbrorough on the Ichneumonidae.

Labels: environment and ecology, Helpis minitabunda, ichneumonidae, insects, photos, sci-blogs, wasp

Friday, May 28, 2010

Living up to our name

Homo sapiens means "wise man". Sometimes it's hard to think that Linnaeus was right in honouring our species with that name. We're the reason the earth is going through its sixth great extinction; people are still routinely killed for belonging the wrong race, religion or sexuality and the prospect of taking action on climate change makes a significant proportion of the population behave like children. So it's nice to be reminded every now and again about the sorts things our species can do when we put our minds to it. I've been trying to find time to write a proper post about the Neanderthal genome, but here's something to think about on a rainy Friday afternoon.

In 1857 an anatomist and a school teacher, Hermann Schaffhausen and Johann Fuhlrott, described a set of bones that had been discovered in a limestone quarry in what was then called the neanderthal region of Germany. Amazingly, the neanderthal region was named after Joachim Neander whose own name translates as "new man". A new man was exactly what Schaffhausen and Fuhlrott saw in the bones that they described. They were at once human and something "other" Chief among the characters that set the neanderthal samples apart from modern humans was the thick brow ridge that we now think of as characteristic of primitive humans. Thanks to these differences the school teacher and the anatomist concluded that the neanderthal samples were human but something quite different than modern Europeans.

"Neanderthal Man" was the first pre-human fossil to be described. At the time science had no convincing mechanism by which species might change over time and no idea of how organisms passed on traits to their offspring. Within in a couple of years Darwin had published The Origin and Mendel his Experiments on Plant Hybridization (which was promptly ignored, and only cited three times in 30 years). In time scientists discovered more human fossils; Neanderthal man showed up all over Europe and took the name H. neanderthalensis, Euguen Dobois uncovered H. erectus in Asia and host of anthropologists have since added characters like the Turkana boy, H. habilis, Ardi and a whole cast of Australopithecines to our family tree.

The science of heredity moved on too. In the 20th century geneticists, especially Hugo deVries, rediscovered Mendel's work and set about building a particulate theory of inheritance. TH Morgan showed that genes resided on chromosomes, Fisher, Wright Haldane and others synthesized Mendelian genetics with Darwin's ideas on evolution, MacLeod and McCarty showed that DNA (a chemical initially identified by Miescher) contained genetic information (though no one believed them until Hershey and Chase demonstrated it again) and, of course, Watson and Crick showed us what DNA looked like thanks to Rosalind Franklin's x-rays. It took a little over 20 years to get from Watson and Crick's double helix to first complete virus genome and another 30 to scale the 5 orders of magnitude in size between that one and the human genome.

Last month, scientists published a first draft of the Neanderthal genome. 60% of the genetic make up of species of human that has been extinct for thirty thousand years. Thanks to the work of all those scientists listed above, and countless others who go unremembered, we now have a pretty good idea about the genetic basis of the thick brow ridge that convinved Schaffhausen and Fuhlrott than neanderthal man something different than other humans. The Runx2 gene is in a region of the genome that has been selected for in the H. sapiens lineage. We know from the work of yet more scientists that Runx2 is one of the most important genes regulating bone growth in humans and is associated with malformations of the skull. It's no great stretch to imagine that our species lost the brow ridge that that we associate with primitive humans thanks to changes in the expression pattern of Runx2.

It some ways that's a trivial piece of information, we've known for a long time that most morphological change is likely due to changes in the expression pattern of development genes. But isn't it wonderful to think that in the span of two human lifetimes we've moved from knowing nothing of our species' history to the point that we are developing hypothesis on the molecular basis of the changes that made us different from the host of human species we've since discovered.

Labels: evolution, genetics, genomics, Human evolution, human genome, sci-blogs, science

Sunday, May 23, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - Attack of the Killer Sponge!

![]() Chondrocladia turbiformis, a ruthless carnivore hauled from bottom of the sea off new New Zealand by NIWA scientists, has been named among the top ten new species described last year. This abyssal predator isn't a kraken, a plesiosaur that time forgot or even an improbable (but awesome) hybrid. It's a sponge.

Chondrocladia turbiformis, a ruthless carnivore hauled from bottom of the sea off new New Zealand by NIWA scientists, has been named among the top ten new species described last year. This abyssal predator isn't a kraken, a plesiosaur that time forgot or even an improbable (but awesome) hybrid. It's a sponge.

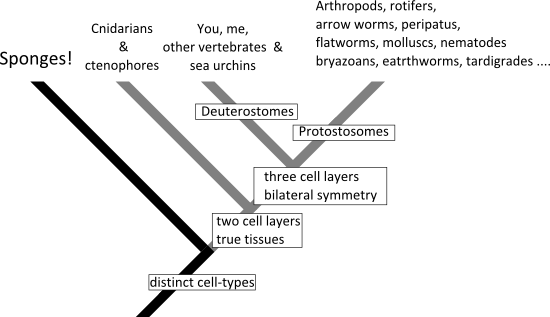

It may come as some surprise that a sponge can be a carnivore, or even that sponges are animals. Sedentary as they are, sponges tick all the boxes for inclusion in the kingdom Anamalia. They eat other organisms to make energy and build their body (differentiating them form plants and algae), they have cells enclosed by membranes (not cell walls like plants and fungi) and they are truly multi-cellular, with specialised cell-types (which sets them apart from protists). On the other hand, sponges are pretty unusual animals. Sponges have no nervous system, no gut, not circulatory system and their cells don't form tissues. The relative simplicity of sponges helps us to understand the evolutionary history of animals, by plotting some of the characteristics of modern animals onto a phylogeny we can see what order those characters evolved in:

So, sponges are useful in trying to understand the evolution of animals. But we shouldn't view modern species as steps along a path toward more complex animals. Sponges are amazing creatures in their own right, for a start they're the only animals that don't have a mouth. Most sponges feed by drawing water into the their body through pores and absorbing bacteria and small algae from that water with specialized cells on the inner surface of their bodies. The cells of the inner surface have two sets of projections to help them with this task. The tail-like flagella which beat together to get water flowing over the absorbing cells and the hair-like micro-villi which increase the cells surface area and make them more efficient absorbers (the guts of more complex animals play the same trick on a larger scale). Most sponges further increase the efficiency of this process by taking the form, and the function, of a chimney. The tubular forms are help together by a mesh of small calcium carbonate structures called spicules.

Filter feeding works well in relatively nutrient-rich shallow waters, but scientists have pulled odd looking sponges up from the bottom of the ocean. Some of those sponges still had the characteristic sponge filter feeding system, but others had lost it all together. Quite how these strange sponges were getting by in the dark and unproductive abyss without even the normal sponge feeding system remained a mystery until 1995 when French researchers found a relative of the deep sea sponges in a relatively shallow submarine cave. Abestopluma hypoa gave scientists their first chance to observe these sponges, and what they saw was amazing: it was a carnivore. In life A. hypoa projects a set of filaments into the water. Those filaments are covered in tiny spicules which act like Velcro (that's the author's own simile) grabbing passing crustaceans and holding them in place. It takes a while for the sponge to get its meal, cells make contact with prey within an hour but the actual ingestion follows a period of cell growth and movement which completely covers the animal after a day. It takes another couple of days to completely digest the crustacean.

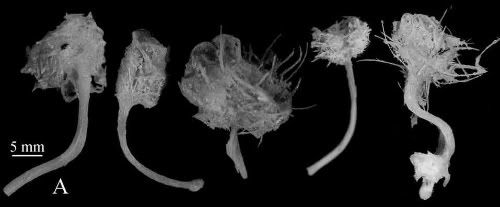

Since that first discovery scientists have discovered many more carnivorous sponges, with a surprisingly large number coming from sea mounts off New Zealand and in the Southern Ocean. The topic of today's post (I knew I'd get to it eventually...), Chondrocladia turbiformis, is one of the newest killer sponges, and it looks a bit like a mushroom:

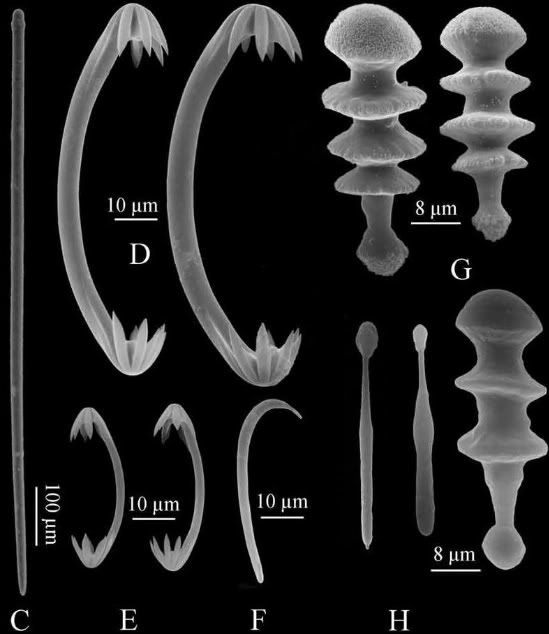

The Chondrocladia are a bit of a special case among the carinovore-sponges because they have retained the rudiments of their filter feeding system. They don't appear to use it to supplement their diet, rather it's been re-purposed to inflate a balloon like structure the sponge uses to help capture prey. (For a stunning example of this structure in a live sponge see the photo that illustrates Olivia Judson's article here.). But the thing that really distinguishes C. turbiformis from the already amazing carnivorous sponges are its spicules:

Beautiful as they are, those symmetrical curved claws in D and E are run of the mill for Chondrocladia. The spinning top spicules in G and H are something quite different. It was only through the description of C. turbiformis and a related species C. tasminae that it became apparent these spicules, with have been named trochirhabds, are present in some modern Chondrocladia species. It's not extactly clear what these cool little spiclues are doing in modern Chondrocladia but they give us a clue to the history of carnivorous sponges. Spicules just like the trochirhabds described from C. turbiformis have been found in marine sediments from the Jurassic period. It appears the carnivorous sponges that it took us until 1995 to learn about have been living in the oceans for at least 150 million years.

Vacelet, J., Boury-Esnault, N., Fiala-Medioni, A., & Fisher, C. (1995). A methanotrophic carnivorous sponge Nature, 377 (6547), 296-296 DOI: 10.1038/377296a0 Jean Vacelet,, Michelle Kelly, & Monika Schlacher-Hoenlinger (2009). Two new species of Chondrocladia (Demospongiae: Cladorhizidae) with a new spicule type from the deep south Pacific, and a discussion of the genus Meliiderma Zootaxa (2073), 57-68

Labels: carnivorous sponge, citizen science, might interest someone, porifera, sci-blogs, sponge, sunday spinelessness, taxonomy

Sunday, May 16, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - You don't know the trouble you're in

A scene from the garden. On the left, the New Zealand Praying Mantis Orthodera novaezealandiae. On the right, a hover-fly that doesn't know how much trouble it's in.

(for those interested in the final result: the hover-fly flew off; the mantis lunged, but missed)

Labels: environment and ecology, hover-fly, might interest someone, Orthodera novaezealandiae, photos, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness

Sunday, May 9, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - Jump!

Surely that's a face that will find its way into even the most hardened arachnophobes heart? The owner of those big round eyes is a female Helpis minitabunda, the Australian Bronze Jumping Spider. Last week I mentioned that the jumping spiders (family Salticidae) where my absolute favourite group of spiders, but the photos I used in that post didn't do much to show just how endearing these spiders can be (even when they are in the process of chomping down on a blowfly!)

Jumping spiders stand apart from most of their kin by being active during the daytime. Like the lynx spiders that have featured here before, they are active hunters which rely on good sight and surprise attacks to keep themselves fed. That lifestyle has led to features that make the jumping spiders so cute, huge forward facing eyes and a head that swivels around to follow you. Most spiders will react to an intrusion from some lumbering fool sticking a camera lens in their face by running away. Not jumping spiders, they'll eye you up in much the same way they would a passing beetle:

I managed to take a few photos of jumping spiders while I had all that fancy camera gear to play with. These photos don't do justice to the gear or their subjects, but here's a closer look at a couple of tropical jumpers (probably a female and then a male from a Menemerus species):

If my hunch about those two photos representing one species is right, then I've shown you photos of two species here. Hardly a fair sampling of the 5 000 currently described species of jumping spiders (about as many species as all the mammals put together). Those two species are relatively drab, but jumpers come in some amazing colors. Thankfully, photographers with much more skill than I have recorded some of that diversity. Ted MacRae recently linked to Thomas Shaha's focus stacked invertebrate photos which include some of the most amazing jumping spider photos I've ever seen and Ugly Overload wronged the group by including a montage of jumping spiders on their pages.

A wee update: Another local blogger has been talking about jumping spiders lately, Alan Macdougall had a Trite auricoma pay him a visit, check out his neat photos here.

Labels: arachnophilia, environment and ecology, Helpis minitabunda, jumping spiders, photos, sci-blogs

Wednesday, May 5, 2010

Memorialising my own folly

I'm usually a pretty cautious kind of a guy. I might be physically incapable of proofreading but I at least think these posts through and make sure I'm not committing any grave errors of science before I hit the publish button. Usually.

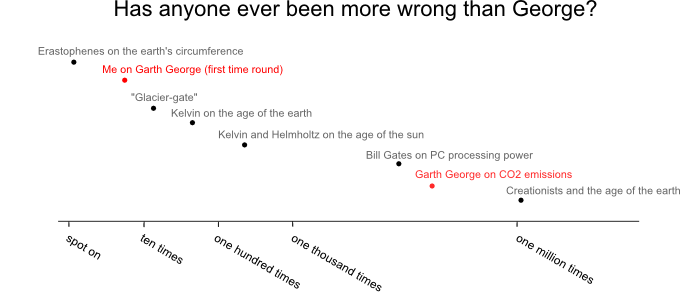

A couple of weeks ago I made fun of Garth George because he underestimated New Zealand's carbon emissions by some staggering amount. It turns I overestimated the degree of Garth George's underestimate. Or to put it another way, I screwed up that maths. Garth George is still spectacularly wrong, out by a factor of 375 000, but I had said he was out by about eight times more than that. In putting the graphics together I'd written down the inverse of George's error (about 2.75 millionths, or 2.75 x 10-6) to help me calculate the sizes for each triangle and when it came time to write up the post I mistook my notes, reading 2.75 x 106 or 2.75 million.

That's not an excuse, it should have been obvious to me, as someone who passed 3rd from maths, that 3.7 x108 couldn't be millions of times bigger than 1 x103 and in writing the post I should have caught it. It's all very embarrassing, but if you are going to make fun of people you have to be prepared to be treated in the same way. So, in that spirit, here's the magnitude of my error plotted for all to see:

And the worst bit, Garth George is still among the wrongest people in history but not quite on the same level as the Young Earth Creationists (and will no doubt be overtaken by Bill Gates at some stage, if he really said that thing they say he said):

Any physical science types reading this post might want to make a joke at the expense of biologists now, can I suggest this one:

A group of biologists and a group of mathematicians meet each other at a train station on their way to a conference on ecological modeling. The biologists each line up to buy a ticket, while a single mathematician collects a few coins from each his colleagues and buys a single ticket. Both groups board the train and before the biologists can ask what the mathematicians are up to one of them yells out that the conductor is on his way. The mathematicians leave on mass, cramming into one bathroom. The conductor arrives and clips the ticket of each biologist before knocking on the bathroom door and asking “tickets please”. The mathematicians slide their single ticket under the door, it gets clipped and the mathematicians get their train journey at a fraction of the cost the biologists paid.The two groups run into each other again on the way home from the conference. This time the biologists are on to the game, so after exchanging a knowing wink with the mathematicians they send a representative off to get one ticket. But they are amazed to see the mathematicians don’t even bother with the single ticket that bought for the first journey. The biologists want to know what’s going on by the mathematicians stay tight lipped until their spy announces “conductor on his way”. The biologist scramble just as they’d seen the mathematicians do on the last trip, squeezing into a bathroom. In contrast, all but one of the mathematicians strolls down to the other bathroom in the train while the other approaches the biologists’ room, knocks on the door and asks “tickets please”.

(The moral of the story, biologists should think carefully before applying mathematical methods)

Labels: blerg, blog blogging, climate change, might interest someone, sci-blogs

Sunday, May 2, 2010

Sunday Spinelessness - A beach spider

A very quick post from me today, I've spend the weekend at the first Genetics Otago postgraduate retreat. Which was here:

Obviously, the meeting was mainly about talking with members of the most conspicuous vertebrate species on earth, but I did get a couple of chances hunt out some spineless creatures. My favourite has to be this guy, one of a few jumping spiders I found on saturday morning, sunning themselves on rocks high up on the beach:

The jumping spiders (Salticidae) are absolutely my favourite spider family, it's almost impossible not to anthropomorphise their huge round eyes and swiveling heads. Thankfully, once "my" jumping spider had calmed down he turned around and posed for me.

Labels: arachnophilia, citizen science, environment and ecology, jumping spiders, photos, Salticidae, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness